Executive summary

Research and practice on the gender dimensions of efforts to prevent and counter violent extremism (P/CVE) are limited. Comparatively little P/CVE work takes account of women’s experiences and needs, and most programmes are designed with men in mind. However, there is a growing recognition of the need to take account of the gender dynamics of violent extremism, including in relation to preventative work. Programmes are beginning to be designed for women and research is starting to more systematically examine how to understand the gender dynamics implicated in violent extremism and efforts to respond to it.

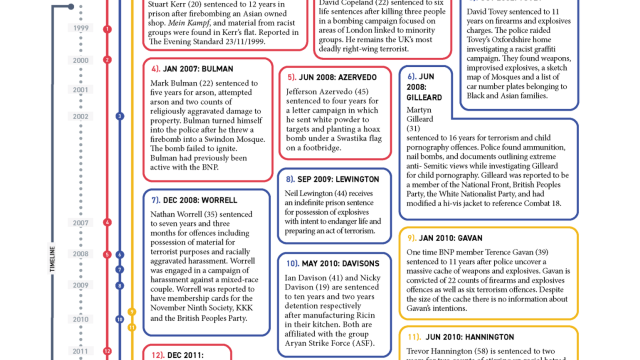

This report reviews research on P/CVE interventions that explicitly focus on women. It is organised by the three tiers of intervention commonly used to describe P/CVE work: primary interventions which work at the community level to prevent involvement in extremism; secondary interventions that engage with those identified as being at risk of involvement; and tertiary interventions designed for those convicted of terrorism offences or believed to be directly engaged in violent extremism. It identifies key learning by looking at a series of international case studies and reflects on the next steps for this research agenda.

Key findings

General

- ‘Gender blind’ programmes remain the norm. Relatively few initiatives take gender into account when designing and delivering interventions, and there are comparatively few P/CVE intervention programmes tailored to women.

- There is very little research relating to interventions specifically designed for girls.

- Those P/CVE programmes for women that do exist mainly focus on Islamist-related terrorism.

- Embedding gender into the development of P/CVE programming – for example, by ensuring women contribute to both the development and delivery of interventions – has the potential to support positive outcomes.

- Interventions should avoid instrumentalising women’s roles in P/CVE and instead seek to engage with women meaningfully, constructively, and over the long term.

- Interventions are varied in their target and approach. They range from programmes targeting broad societal-level issues such as gender inequality, to community-level initiatives enacted in the context of women’s civil society groups, programmes directed at state institutions such as the police or government departments, as well as projects that work with small groups or individual women.

- Participatory approaches which engage with grassroots actors have the potential to provide sustainable, independent ways of diverting and supporting women away from violent extremism.

- The field will benefit from more experienced practitioners able to work with women involved in extremism.

- The evidence base on what works to divert women and girls away from violent extremism is weak.

- There is a need for more methodologically robust and empirically informed research to inform assessments about the effectiveness of interventions in general, and in particular in the context of P/CVE programmes designed for women.

Primary interventions

- The aims of primary interventions focused on women and girls are diverse and include enhancing trust in statutory authorities; mitigating the influence of extremist groups, developing more resilient communities; improving the treatment of women in society; and creating educational and employment opportunities.

- Initiatives that are responsive to local needs and which take a pluralistic approach, delivering different kinds of activities – including supporting women’s economic situation; providing training and education; and increasing opportunities for women to engage in political and community life – seem to provide the greatest chance of success.

- Training and education initiatives have the potential to develop women’s confidence about engaging in P/CVE work when they are targeted appropriately and developed in gender-sensitive ways.

Secondary interventions

- Secondary interventions that work with those at risk of radicalisation are often overseen by statutory agencies in the context of case-managed interventions offering tailored support based on an individual assessment of needs.

- Engaging with hard-to-reach women is enabled through long-term programmes able to draw on pre-existing networks which can access those who are disengaged from the community.

- Some of the factors influencing the likely success of online interventions include the perceived credibility of the interlocutor; how committed the person is to extremism (the more committed, the less likely they are to be persuaded); and the extent to which the messages resonate with the target audience.

- Online interventions benefit from being tailored based on gender-sensitive research into the target audience’s preferred communication style, subject (e.g. political, community, personal), platform (e.g. Facebook, WhatsApp), and forum (e.g. closed or open groups).

Tertiary interventions

- Tertiary interventions are rarely tailored to address women’s needs and experiences.

- Very limited research exists on tertiary interventions designed for women, including those returning from conflict zones.

- Disengaging from extremist groups can be a long-term process, which is most helpfully supported through multiple interventions, targeting different issues in a way that is sequenced appropriately and tailored to an individual’s specific needs.

- Women with children require tailored support to address the complex needs of families with women who have been involved in extremism.

- Women face particular barriers to reintegration due to the stigma associated with their involvement in extremism and because they have transgressed gendered norms.

Multi-agency approaches

- Although evidence remains limited, current good practice suggests that community-focused interventions benefit from being inclusive and collaborative, engaging with multiple stakeholders including women, young people, and civil society organisations.

- Co-designing programmes can foster inter-agency cooperation and understanding as well as helping P/CVE initiatives respond meaningfully to local contexts.

- Intervention providers benefit from being able to develop positive relationships with the individual and their family to provide tailored support in the context of multi-agency working.

- Civil society organisations and non-government organisations can engage with at-risk women in online and offline settings and are important partners in P/CVE work.

Challenging assumptions

- Several stereotypes are highlighted in the literature which belie the complex and individualised nature of women’s experience of violent extremism. In general, women are considered more peaceful and less of a security threat; thought of as victims rather than active agents in extremism; and believed to have different kinds of motivations to men. Most of these assumptions are contested.

- Women’s roles within the family are often assumed to provide opportunities for early intervention. However, the evidence for this is unclear.

- Programmes working with women in their role as mothers should avoid reinforcing gender stereotypes and explore the role of fathers and masculinity in P/CVE.

Understanding women’s experiences

- Efforts to encourage women’s economic empowerment in the context of the P/CVE agenda will benefit from acknowledging the barriers created by the burden of domestic work that women carry and the gender norms and discriminatory attitudes that limit women’s opportunities to engage in P/CVE work.

- Trust in authorities is a key factor in women’s willingness to refer friends and family members they are concerned about. Interventions able to increase women’s confidence and trust in statutory bodies are therefore important.

- Violent extremist organisations and ideologies often reflect specific types of gender norms that need to be considered in intervention work, as these can influence women’s motivation to engage in extremism, and the barriers to reintegration.

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2024 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)