Introduction

Throughout their careers, police officers are exposed to an estimated 900 traumatic events, which, coupled with organisational stressors, contribute to mental ill-health and psychological trauma.

Repeated exposure to work-related traumatic incidents, impedes the ability for many police officers to cope, with the concurrent risk of developing psychopathology and moral injury.

According to the College of Policing, continual exposure to viewing thousands of images of child abuse that creates an environment in which burnout, compassion fatigue and secondary trauma become more likely.

The purpose of the study was to explore moral injury in police online child sex crime investigators. The questions which guided the research asked:

- What are the key features of, and contributing factors to, moral injury in child exploitation investigators?

- How do these manifest in relation to changes in behaviour?

- How can these factors be mitigated?

Moral injury

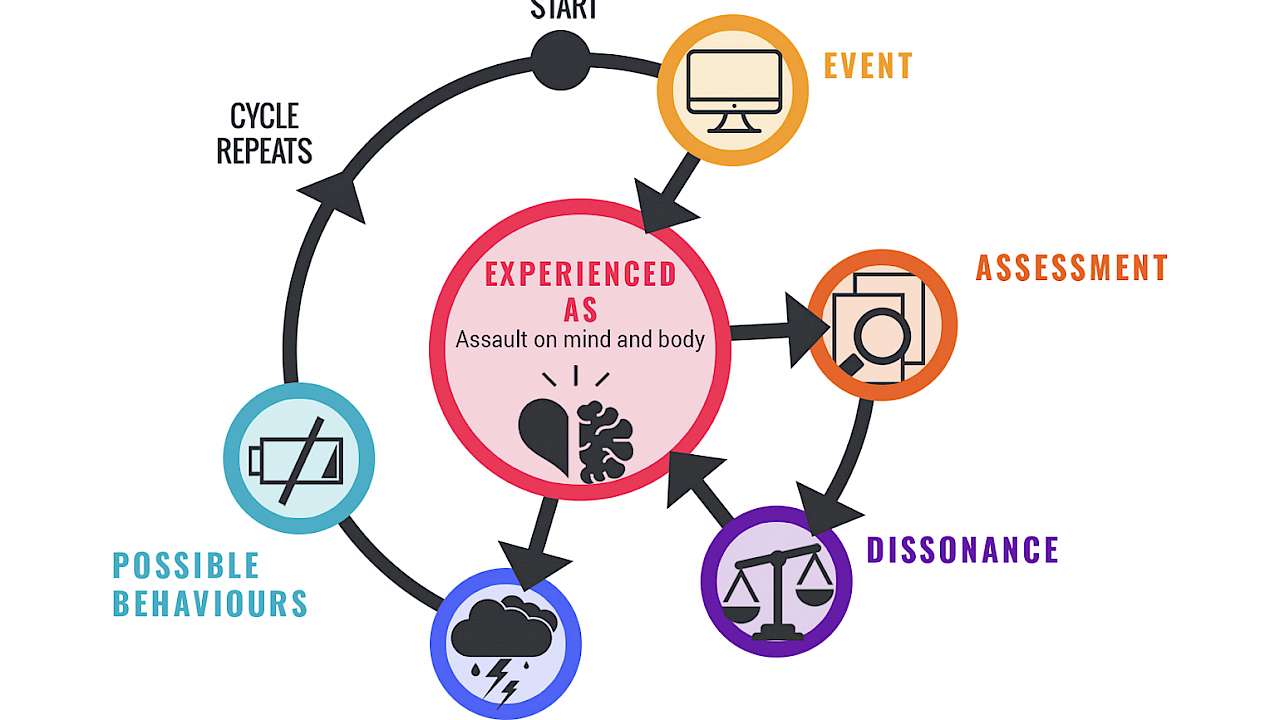

Shay, a psychiatrist who researched with military personnel, defined three characteristics of moral injury; (i) a betrayal of what is morally right, (ii) by someone who holds legitimate authority (iii) in a high-stakes situation. Shay proposed that moral injury was experienced by the body as an assault equivalent to a direct physical attack, with the potential to undermine ‘character, ideals, ambitions, and attachments,’ impairing and potentially destroying trust.

Other researchers found that individual failure to prevent moral violation or witnessing of traumatic life events, ‘transgress[ed] deeply held moral beliefs and expectations’, placing responsibility with individual action. Such subjective disruption was capable of fragmenting the ethical foundation of being; for example, cultural, organisational and group-based rules about fairness, spiritual or religious beliefs and the value of life.

Experiencing a trauma itself does not inevitably result in moral injury

Moral injury can result in significant psychological distress and has recently been observed within the context of policing. Symptoms of moral injury include guilt, frustration, depression, self-harm, shame, loss of spirituality/religiosity, or a sense of rejection. Experiencing a trauma itself does not inevitably result in moral injury.

Of importance is how individuals integrate their assessment of a traumatic event into their personal schema, since poor integration leads to lingering psychological distress. Avoidance behaviours inhibit successful assimilation, resulting in negative self-appraisal and harmful psychosocial impact of moral conflict.

Interpretation is also intrinsic to the development of a moral injury as this appraisal process determines whether the event generates dissonance with the individual’s moral framework, their worldview, and their actions. Such dissonance is found in police child exploitation investigations where police officers are primarily assigned to watch media footage of children who have been victimised, in the process challenging the foundations of their moral framework.

Moral injury and PTSD

Just as experiencing a potentially morally injurious event does not necessarily lead to moral injury, experiencing a trauma does not inevitably lead to developing PTSD.

Unlike PTSD, moral injury is not classified as a mental disorder. It is a dimensional problem that can have profound effects on critical domains of emotional, psychological, behavioural, social, and spiritual functioning.

Unlike PTSD, moral injury is not classified as a mental disorder.

However, studies of the original events which led to medical presentations for combat-related PTSD have reported that 25–34% result in moral injuries.

Additionally, moral injuries differ from PTSD index traumas related to life threat as they are more strongly associated with emotions that develop after an event rather than emotions experienced during the event.

So, while moral injury often co-occurs with PTSD, the latter, unlike moral injury, is generally conceptualised as a fear-based disorder.

Method

A distinctive characteristic of the work of police child online sex exploitation investigators is that it is screen-based, regularly viewing thousands of images and videos. While extensive moral injury research has been conducted with military personnel, moral injury had not been explored among members of the armed forces whose work – and associated mental harms – is screen mediated.

However, the project Principal Investigator had access to research interviews he conducted previously with Royal Air Force Reaper (drone) crew members about their work and its impacts on them. The original research ethics approvals allowed for those interviews to be reanalysed in relation to the moral aspects of RAF Reaper operations where traumatic scenes and imagery were viewed regularly. This police-focused project, therefore, started with a review of moral injury literature to identify its key characteristics.

A thematic analysis of 10 RAF Reaper operator interviews was then carried out, identifying indicators of moral injury in this screen-mediated RAF operational environment. Insights from both the literature review and from the analysis of the Reaper operator interviews were then used to frame the research questions to be used to study the experiences of the police online child sex crime investigators.

The topics which were explored included: the potential for moral injury, belief change, and psychological distress. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) was used to focus the analysis on the lived experiences of online investigators and the factors that contribute to moral injury, belief change and psychological distress.

A purposive sample of six Internet Child Abuse Team members (ICAT) was recruited from two constabularies in the United Kingdom. Semi-structured interviews, with a planned duration of between 60–90 minutes were conducted and subsequently analysed.

Data analysis and selected findings

Verbatim transcripts of the police interviews served as the raw data. During analysis, the data were gathered under four primary themes:

- Impact of organisational role and environment

- Influences of role on identity

- Mechanisms to manage distress

- Influences of trauma on personality, self, and wellbeing.

Between three and five subthemes emerged under each of these primary themes. Selected findings include:

Psychological review and professional support are needed to ensure the psychological wellbeing of all staff. Yet, the participants’ narrative suggested that present support systems are not ‘fit for purpose’ (MI7541), advocating the need for further change. Fear was expressed that seeking help for mental health disorders may bias future career opportunities or undermine the ICAT officers’ professional profile.

A positive element was the keen sense of achievement when a successful prosecution was obtained and they had been able to enact their protectionist values.

The role appeared to have a considerable influence on the identity of investigators and their sense of self. Detaching their professional identity to a home identity was particularly problematic. This incongruence was amplified by hypervigilance resulting from a suspicion of others founded on experiences at work. Interviewing perpetrators amplified such feelings, of importance since identity incongruence is a key factor in psychological distress.

Part of the attraction to the role of being an online investigator was making a difference to society and protecting others.

Some investigators used moral values as a protective tool that shielded them from the traumatic content they were exposed to. For others, misplaced, heightened empathy towards perpetrators was used to normalise extreme emotional disjuncture about moral acceptability.

Family support was observed to be crucial, unrecognised support for online investigators and a substantial buffer for psychological distress. Likewise, peer support emerged as crucial to the psychological wellbeing of ICAT officers, their colleagues are alone in understanding the full implications of the role, supporting prior research by Lepore, that positive and supportive environments can help individuals to manage distress.

Not all coping mechanisms were adaptive or helpful. Cognitive avoidance was used as a deliberate strategy to avoid distressing thoughts, however, these would inevitably present as intrusive thoughts and images reflective of the content observed at work. Shutting off emotion and empathy through detachment also resulted in difficulties with emotional regulation. All of the participants believed that their role was not sustainable, burnout being not a question of “if” but “when”.

The two worlds described by the participants defined the divide between exposure to depravity and the preservation of innocence. The participants articulated the desire to protect their loved ones’ from the dark side, possibly as their goodness represented an essential oasis for the police officers. Because of continual exposure to indecent images of children, many investigators feared that they were contaminated by this dark world, describing it as a virus that isolated them from others.

Several individuals believed they had become more cynical in their attitudes towards other people, fearing the impact of this on their view of humanity. Such skewed perspectives were observed as changes in identity. Developmental trauma including severe physical abuse and neglect, sexual abuse and domestic violence significantly affected the participants’ resilience to viewing graphic images, making them vulnerable to psychological distress.

Understandably, the role had a considerable impact on being a parent and family member, exposure to the horrors of child abuse pushing parents towards protective practices to safeguard their offspring from exploitative situations.

Recommendations

Based on the findings, several recommendations for further research are set out. These involve collaboration between researchers, relevant and expert stakeholders – including policymakers, wellbeing representatives, and ICAT officers – to further explore the difficulties faced by those who are exposed to screen mediated harm, in the design and testing of contextually appropriate and grounded support interventions. These include:

- A quantitative, pilot study of ICAT investigators across police forces within the United Kingdom to explore the frequency and severity of the main harms and concerns articulated by the participants in this current study.

- Designing and trialling of a psychoeducation training programme for managers and peers.

- Evaluation of diverse support interventions such as CBT, person-centred interventions and compassionate mind-based therapies to understand which is best suited to respond to the needs of ICAT investigators in the context of their role.

- A qualitative investigation into the effects of trauma and moral injury on ICAT officers in retirement.

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2024 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)