Introduction

This study concerns the ability to adapt to changeable or uncertain situational demands.

Adaptability is critical for law enforcement and security officers who have to complete specific objectives when interacting with sources within criminal communities (i.e. covert law enforcement).

Although the importance of adaptability for social interactions has been highlighted in several fields, it remains understudied in the context of police work.

Furthermore, despite extensive conceptual work on adaptability, no behavioural measure to evaluate the efficacy of adaptive responses exists.

This study remedies this by relating behavioural indicators of adaptability with subjective adaptability, the quality of the relationship (i.e. rapport and trust), and goal achievement.

The experimental test

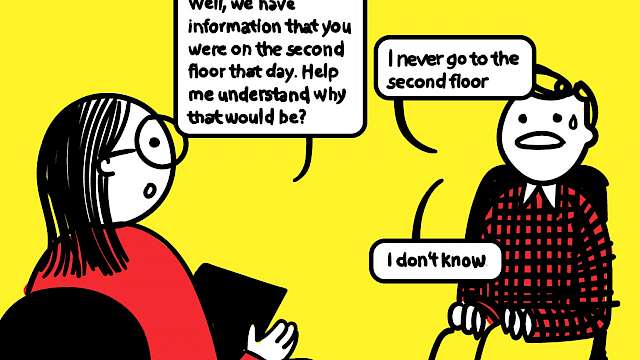

To examine adaptive behaviour, we developed a novel experimental set-up inspired by observations of undercover training at the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD).

In Experiment 1, university students (n = 30) acted as agents that had to complete three undercover missions. Adaptive behaviour was elicited by three features:

- A goal (e.g. the agent was tasked with collecting a secret note hidden in the office of a professor).

- An expectation (e.g. the agent was told that the professor is friendly towards motivated students).

- A violation of that expectation (e.g. the professor is on leave but an assistant is in his office). This violation creates the unexpected situation that the agents must adapt to achieve their mission objective.

Adaptability was measured on the self-rated adaptability scale, as well as by the behavioural adjustments made in response to the changing situational demand.

In Experiment 2, practitioners (n = 22) experienced in covert policing watched four video recordings from Experiment 1 and rated the adaptive responses.

Main findings

Although this study was a first explorative attempt to study behavioural adaptability, we tentatively suggest three preliminary conclusions:

- Providing agents with a specific instrumental objective (e.g. to collect the fingerprints of a study advisor) may lead to adaptive behaviour associated with a reduced relationship with those they interact with.

- Practitioners seem to consider adaptability as being more a feature connected with the quality of the relationship than a feature for accomplishing mission objectives.

- Practitioners should – but do not – take the time spent on each adjustment into account when assessing adaptability in novel and uncertain situations.

Assessing adaptability

Our findings suggest that adaptive behaviour may be tailored to its objective. That is, providing trainees with a purely instrumental objective (e.g. to collect a secret note) may reduce their capacity to consider relational objectives (e.g. to establish rapport) and vice versa.

We thus recommend informing trainees about both relational and instrumental objectives during their training. Otherwise, there is a risk that they underperform on one objective simply because they misunderstand what is expected of them.

However, by informing trainees on the importance of both these objectives you will be in a better position to assess their true qualities, as it will be clearer when specific qualities are lacking.

A behaviour predictive of success

Our findings suggest that agents that are successful at attaining mission objectives in changing situations spend less time on ineffective behaviour. This finding provides a starting point in the search for behavioural indicators of adaptability.

A thorough examination of such behavioural adjustments may be key for contextual assessments of adaptability.

Future research

The primary contribution of this research is the development of a clinical testing procedure that complements authentic training scenarios. For example, by altering mission specifics within the schematic set-up of an objective, expectation, and violation, we can examine an array of situations relevant to covert law enforcement.

It would be particularly interesting to design scenarios in which field experts are tested when interacting with more street-smart subjects. This would allow us to study principles of adaptive expertise, which would help advance training programs and personnel selection.

Read more

- Bernieri, F. J. (1991). Interpersonal sensitivity in teaching interactions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17, 98–103

- Brimbal, L., Kleinman, S. M., Oleszkiewicz, S., & Meissner, C. A. (2019). Developing rapport and trust in the interrogative context: An empirically-supported and ethical alternative to customary interrogation practices. Interrogation and Torture: Integrating Efficacy with Law and Morality

- Collie, R. J., & Martin, A. J. (2016). Adaptability: An important capacity for effective teachers. Educational Practice and Theory, 38, 27–39

- Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., & LePine, J. A. (2007). Trust, trustworthiness, and trust propensity: A meta-analytic test of their unique relationships with risk taking and job performance. Journal of applied psychology, 92, 909–927

- Fahsing, I. A., & Ask, K. (2018). In search of indicators of detective aptitude: Police recruits’ logical reasoning and ability to generate investigative hypotheses. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 33, 21–34

- Klein, G., Klein, H. A., Lande, B., Borders, J., & Whitaker, J. C. (2014). The Good Stranger frame for police and military activities. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting (Vol. 58, No. 1, pp. 275–279). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications

- Jung, J. M., & Kellaris, J. J. (2004). Cross‐national differences in proneness to scarcity effects: The moderating roles of familiarity, uncertainty avoidance, and need for cognitive closure. Psychology & Marketing, 21, 739–753

- Mayer, R. C., & Davis, J. H. (1999). The effect of the performance appraisal system on trust for management: A field quasi-experiment. Journal of applied psychology, 84, 123–136

- Martin, A. J. (2017). Adaptability – what it is and what it is not: Comment on Chandra and Leong (2016). American Psychologist, 72, 696–698

- Martin, A. J., Nejad, H., Colmar, S., & Liem, G. A. D. (2012). Adaptability: Conceptual and empirical perspectives on responses to change, novelty and uncertainty. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 22, 58–81

- Martin, A. J., Nejad, H. G., Colmar, S., & Liem, G. A. D. (2013). Adaptability: How students’ responses to uncertainty and novelty predict their academic and non-academic outcomes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105, 728–746

- Power, N., & Alison, L. (2019). Decision inertia in critical incidents. European Psychologist, 24, 209–218

- Pulakos, E. D., Arad, S., Donovan, M. A., & Plamondon, K. E. (2000). Adaptability in the workplace: Development of a taxonomy of adaptive performance. Journal of applied psychology, 85, 612–624

- Spiro, R. L., & Weitz, B. A. (1990). Adaptive selling: Conceptualization, measurement, and nomological validity. Journal of marketing Research, 27, 61–69

- Taylor, P. J. (2002). A cylindrical model of communication behaviour in crisis negotiations. Human Communication Research, 28, 7–48

- Ward, P., Gore, J., Hutton, R., Conway, G. E., & Hoffman, R. R. (2018). Adaptive skill as the conditio sine qua non of expertise. Journal of applied research in memory and cognition, 7, 35–50

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2024 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)