Over the past two decades, an ever-evolving series of anonymous image-board forums knowns as ‘chans’ have proliferated on the internet, with 4chan being the most well-known of them all.

Although these online forums contain a wide variety of content, including discussions of subjects from cooking to video games, they quickly drew the attention of observers due to the more extreme – and sometimes illegal – content they host (extremist ideological material, fetishist/child pornography, weapons instructions, etc.).

Scrutiny increased following a spree of far-right inspired attacks in 2019, including Brenton Tarrant’s attack of the Christchurch mosques, whose perpetrators used the so-called ‘/pol’ (‘politically incorrect’) board of one of the chans (8chan) to announce their attacks, promote their manifestos, and/or share the live recordings of their crimes.

Concerns have grown that /pol boards function as radicalising echo-chambers and constitute gateways to more radical content, and thus occupy a particularly problematic position within the broader far-right online landscape.

In response to this, a research team has analysed several notorious /pol boards to specify the type of extremist interactions hosted by these forums; better understand the role they play in the far-right online ecosystem; and suggest how best to mitigate the threats posed by them.

This guide gives a summary of the team’s analysis, findings and policy recommendations.

Analysis

The research team – Drs Stephane Baele, Lewys Brace, and Travis Coan from the University of Exeter, scraped the content of six /pol boards over more than six months, using custom Python coding.

The textual and visual content of the boards was organised in a database that also included relevant metadata (date/time of posts, length of posts, etc).

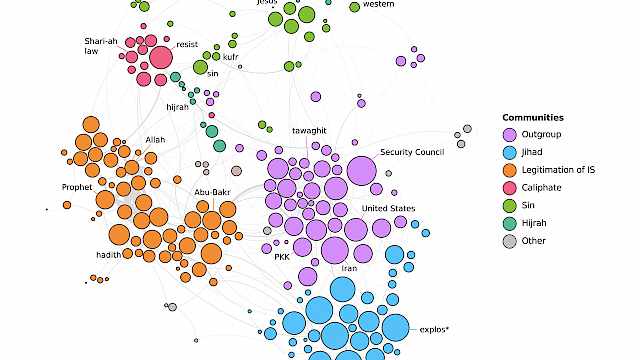

The analysis relied on a series of computer-assisted content analysis methods such as co-occurrence networks, correspondence analysis, or hyperlinks detection.

/pol boards analysed

4chan/pol 8kun/pol 6chan/pol Endchan/pol Infinitychan/bestpol* Neinchan/pol* *accessible only on the dark web

Findings

1. The boards exist in a three-tier system

A three-tier model was derived from a qualitative assessment of the quantitative datasets by the research team. A board’s position within the model is determined by, simultaneously, the volume of its posting traffic and the extremity of its content. See table below.

| Tier 1 | Tier 2 | Tier 3 |

|---|---|---|

| 4chan/pol | 8kun/pol | All other boards |

| High levels of posting traffic and less-extreme content than 8kun/pol. | Much less traffic than 4/chan/pol but significantly more racist content. | Comparatively very little traffic but the most extreme content, usually openly neo-Nazi or fascist. |

2. The boards act as a gateway to far-right online content

The three-tier model also derives from the many external domains that are linked to in posts. Contributors to Tier 3 boards post proportionally more links to far-right websites and content than those in Tier 2, who themselves post proportionally more than Tier 1 contributors. Additionally, linked far-right websites and con

Recommendations

- Law enforcement and security practitioners should not give each board the same level of attention

While 4chan/pol in Tier 1 is by far the most popular board and its content may be distasteful, in a context of limited resources it is advisable to focus attention on boards in Tiers 2 and 3.

While the boards in Tier 3, such as Infinitychan/bestpol and Neinchan/pol, contain more extreme content and more developed ideas, 8kun/pol in Tier 2 should be the focus of granular analysis. Despite it being possible that the right-wing terrorists listed in the table below visited Tier 3 boards, engagement with these boards is minimal and the anecdotal data available from these cases indicates that the majority of their radicalisation happened on 8chan/pol.

| Date | Suspect | Location | Announcement method |

|---|---|---|---|

| 27/10/2018 | Robert Bowers | Pittsburgh, USA | Post to Gab |

| 15/03/2019 | Brenton Tarrant | Christchurch, New Zealand | Post to 8chan |

| 27/04/2019 | John Earnest | Poway, USA | Post to 8chan |

| 03/08/2019 | Patrick Crusius | El Paso, USA | Post to 8chan |

| 10/08/2019 | Philip Manshaus | Bærum, Norway | Post to Endchan |

| 09/10/2019 | Stephen Balliet | Halle, Germany | Post to Meguca |

Table 1: High-profile attacks linked to chan sites during late-2018 to early-2020. Note: Meguca is also a chan-like image board

This working assumption is supported by the team’s content analysis. Specifically, as one progresses from Tier 2 to Tier 3, the boards start to exhibit a more heterogeneous assemblage of different themes linked to far-right concerns, which partly stems from their low popularity. This may result in less of a group identity than what is at play on 8kun/pol and 4chan/pol. These boards are consequently less of a ‘radicalising force’ despite their more extreme content, which is already at the most extreme end of the ideological spectrum.

- Traditional tactics to counter extremist content are unlikely to work

Shutting down the boards can potentially be counter-productive, but only if part of a rapid, sustained and large-scale effort to shut them all down at the same time, and to close any new ones that may appear.

It has been demonstrated at least twice in the last two to three years that, when faced with being shut down, these communities simply migrate to new or dormant chans – all implement the same HTML structure and are very easy to replicate.

The possibility of migration to other platforms, such as Discord servers, also exists. While one such migration is easy to implement, multiple migrations inevitably incur costs and risks to their extremist users: internal strife may erupt, user bases may fragment to more than one successor platform, enthusiasm may wane, etc.

Attempts to shut down these platforms come with a risk for practitioners. Given the role they play as gateways to the wider far-right online ecosystem, shutting them down diminishes useful intelligence into what other communities and domains exist in this area.

This recommendation should be viewed in the context of the ‘hydra effect’ nature of these chan sites and their insertion within a much larger landscape of fringe discussion spaces (slug.com, kiwifarm, etc.).

In conclusion, shutting down these sites should only be done as part of a sustained and large-scale effort (such as the one conducted in December 2019 by Europol’s IRU on ISIS Telegram channels), and only after considering the potential migration effects and resulting loss of intelligence.

- Providing counter-narratives in the /pol boards is unlikely to work

Providing counter-narratives is unlikely to work for similar reasons as to why the US’ Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) 2013 ‘Think Again, Turn Away’ campaign failed: source credibility.

While this counter-narrative programme did recognise the key role that social media was playing in ISIS’ online recruitment, it did little more than provide a platform for ISIS sympathisers and members to mock the DHS and sow an increased distrust in US foreign policy.

The issue of source credibility is particularly problematic when dealing with the chans, for two reasons:

- The user base is instantly suspicious of any poster who does not use the very specific language and unwritten interaction codes of the group, both with regards to terminology and memes.

- The user base is highly paranoid about being researched and surveyed. Any substantial belief of this occurring, such as counter-narratives appearing, would trigger rejection or, if sustained, platform migration.

There are also practical concerns that should be considered before any counter-messaging campaign is proposed. For example, researchers should not underestimate how tech-savvy some of the users are.

If the office IP address is not masked, the user base has shown themselves capable of determining that they are under surveillance due to how a particular IP address is only posting suspicious messages during office hours.

- Innovative tactics are warranted

Given the limitations of traditional tools, more out-of-the-box tactics should be considered. One such tactic would aim at gradually making these boards less interesting for their users.

One way to achieve this would be to regularly post content that looks genuine (using the right language, imagery, etc.) yet is meaningless – this would dilute the message of these boards and make their threads uninteresting, thereby reducing their attractiveness and sense of community.

Recent developments in artificial intelligence enabling researchers to automatically generate credible extremist sentences make such a tactic cheap and easy to implement.

Academic Publications

The ‘tarrant effect’: What impact did far-right attacks have on the 8chan forum?

This paper analyses the impact of a series of mass shootings committed in 2018–2019 by right-wing extremists on 8chan/pol, a prominent far-right online forum. Using computational methods, it offers a detailed examination of how attacks trigger shifts in both forum activity and content. We find that while each shooting is discussed by forum participants, their respective impact varies considerably. We highlight, in particular, a ‘Tarrant effect’: the considerable effect Brenton Tarrant’s attack of two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, had on the forum. Considering the rise in far-right terrorism and the growing and diversifying online far-right ecosystem, such interactive offline-online effects warrant the attention of scholars and security professionals.

Baele, S. J., Brace, L., & Coan, T. G. (2020). The ‘tarrant effect’: What impact did far-right attacks have on the 8chan forum? Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 1–23. [SB2] .

Read more

- Stephane J. Baele, Lewys Brace & Travis G. Coan (2020) The ‘tarrant effect’: what impact did far-right attacks have on the 8chan forum?, Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, DOI: 10.1080/19434472.2020.1862274

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2024 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)