Effective public communication can help prevent attacks on crowded places by encouraging reporting. It can also reduce the impact of attacks that it was not possible to prevent by informing the public about how to protect themselves. Despite this, there has historically been limited research on the impact of communication campaigns on public perceptions of the likelihood or risk of terrorist attacks, or the effectiveness of the messaging in informing protective health behaviours prior to or during an attack.

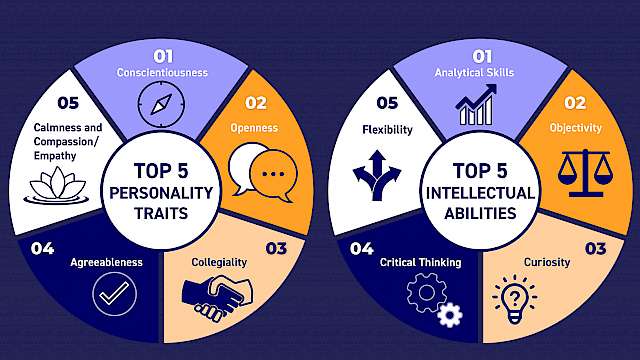

Our research applies theories of risk perception, risk communication and health psychology to explore the effectiveness of existing campaigns in preventing attacks by increasing reporting behaviours (e.g. ‘See it, Say it, Sorted’) and protecting life by increasing the likelihood of members of the public engaging in protective health behaviours (e.g. ‘Run, Hide, Tell’) when an attack occurs.

See It, Say It, Sorted

Pre-event communication is often understood in terms of providing information about protective actions that can be taken when an event occurs. Pre-event communication in a counter-terror context also has the potential to prevent a terrorist attack from taking place. We used a survey experiment to examine the impact of communication campaigns designed to encourage public vigilance and reporting on railways.

Results indicate that the ‘See It. Say It. Sorted’ campaign is effective in encouraging members of the public to report suspicious behaviour in train stations. However, in addition to reporting suspicious behaviour to a member of rail staff or a police officer, as requested, most respondents answered that they would also consider reporting to a member of staff in the concourse café. This highlights the importance of providing all members of staff with training on how to respond to reports, rather than only training those directly responsible for security.

Results also suggest that future public vigilance campaigns should address differences in lay and official definitions of suspicious behaviour to reduce uncertainty as a barrier to reporting, and include guidance about specific suspicious behaviours to increase reporting intentions. Specifically, our work brings further evidence to bear on previous studies indicating that members of the public tend to focus on more familiar, traditional criminal activity such as pick-pocketing or car theft.

In contrast, individuals are less willing to report terrorism-related behaviours if they are uncertain about the relationship between the behaviours and attack planning. Drivers such as the perceived benefits of reporting are particularly important for increasing the likelihood of reporting suspicious behaviour on rail networks.

Run, Hide, Tell

The UK National Police Chiefs’ Council released a Stay Safe film and leaflet including ‘Run, Hide, Tell’ guidance for members of the public in 2015 in response to marauding terrorist attacks in Paris, France. Other countries, such as Denmark, did not provide this type of pre-event communication due to concerns about scaring the public. We conducted three survey experiments, which demonstrated that ‘Run, Hide, Tell’ guidance does not increase perceived risk from terrorism. It does, however, increase trust by increasing public perceptions of security services’ preparedness to respond and the perceived quality of police advice for keeping people safe during an attack.

Our research also found that ‘Run, Hide, Tell’ has a positive impact on encouraging protective behaviours (e.g. immediately running to find a hiding place) and reducing public intention to engage in risky behaviours (e.g. calling someone who may be hiding during an attack).

A one-year follow-up study demonstrated some reduction in positive impacts of the guidance over time.

However, it also highlights the need for future communications to address perceived response costs and target specific problem behaviours. A one-year follow-up study demonstrated some reduction in positive impacts of the guidance over time.

For example, one year on, people were more likely to call someone who may be hiding during an attack than they were following initial receipt of the guidance. However, people who previously received the guidance remained more likely to adopt protective health behaviours and less likely to engage in such risky behaviour than those who had not received any information.

Run, Hide, Tell vs Run, Hide, Fight

‘Run, Hide, Tell’ remains UK official advice to the public on how to keep safe during a marauding terrorist firearms attack. However, in 2018 Norwegian security authorities issued alternative guidance to the public to ‘Run, Hide, Fight’. The recommendation to ‘fight’ as a last resort is consistent with the US approach and informed by experience from the 2011 Utoya attack, which demonstrated that it is not always possible to avoid confrontation.

We were interested in understanding the potential benefits and unintended negative consequences of each of these campaigns. Would, for example, the UK approach discourage people from taking action as a last resort or would the Norwegian guidance encourage people to adopt risky behaviours in situations where it would still be possible to run?

Our research provides some support for both campaigns, as both sets of guidance increased public intention to adopt protective health behaviours. However, while we did not find evidence that the ‘Run, Hide, Fight’ campaign encouraged unwanted risky behaviours, our results did suggest that ‘Run, Hide, Tell’ guidance may discourage proactive planning of what to do in the worst-case scenario. This suggests that ‘Run, Hide, Tell’ guidance may benefit from providing additional information on what to do if it is not possible to avoid confrontation.

Recommendations

Our results provide evidence-based, detailed guidance about what counter-terror organisations can do to increase the likelihood of members of the public reporting suspicious behaviour, or following advice when a terrorist attack occurs. Our work addresses practitioner concerns about causing panic or increasing fear by demonstrating that the provision of guidance does not increase the perceived risk of terrorism.

It also demonstrates that communication targeted at increasing public reporting of suspicious behaviour in crowded places is effective if it reduces uncertainty and reinforces the perceived benefits of reporting.

Additionally, communication designed to better enable members of the public to protect themselves if an attack occurs can enhance trust in responding organisations, as well as encouraging protective behaviours and discouraging potentially dangerous actions during a marauding terrorist attack. Unique insights include the need for communicators to:

- Provide training to all staff working in crowded places. Members of the public are likely to report suspicious behaviour to staff working in the shops and restaurants in crowded spaces, as well as security or operational staff.

- Address differences in lay and official definitions of suspicious behaviour to reduce uncertainty as a barrier to reporting.

- Include guidance about specific suspicious behaviours to increase reporting intentions.

- Communicate the benefits of reporting suspicious behaviour.

- Address the perceived response costs associated with following guidance and target specific problem behaviours.

- Provide additional information on what to do if it is not possible to avoid confrontation.

Read more

- Lindekilde, L., et al. (2021). ‘Run, Hide, Tell’ or ‘Run, Hide, Fight’? International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 60(15), 1-9.

- Pearce, J.M., et al. (2019). Communicating with the public about marauding terrorist firearms attacks: Results from a survey experiment on factors influencing intention to ‘Run Hide Tell’. Risk Analysis, 39(8), 1675-1694. doi: 10.1111/risa.13301

- Pearce, J.M., et al. (2019). Encouraging public reporting of suspicious behaviour on rail networks. Policing and Society, 60(7), 835-853. Published online: 19 April 2019. Available at: tinyurl.com/7nnw6bc6

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: ‘See it, Say it, Sorted’ poster.