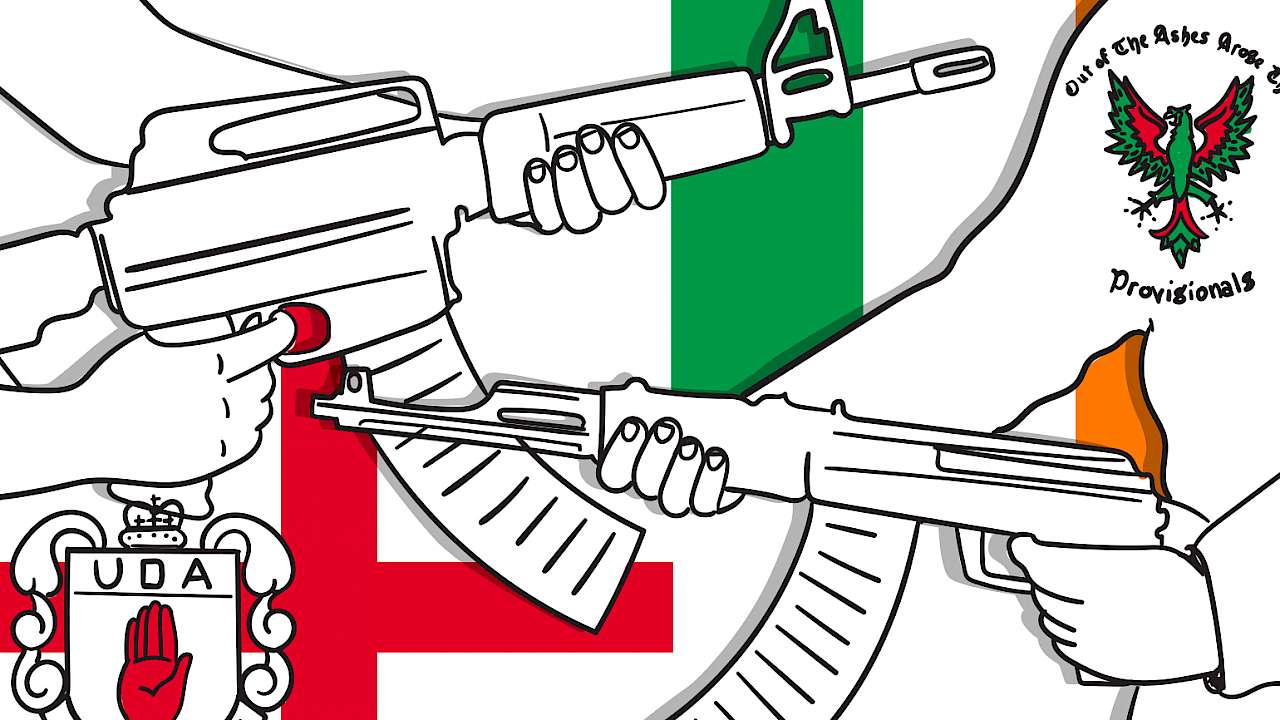

The 12 lessons below are drawn from a reanalysis of interview data from the 1980s and 90s that explored the lifecycle phases among loyalist and republican paramilitaries from across Northern Ireland.

1. Involvement comes before ideology

Being socialised within a family, friendship network and community that was sympathetic and supportive to particular armed groups or their goals was key to creating the conditions for people to gravitate towards armed extremist groups.

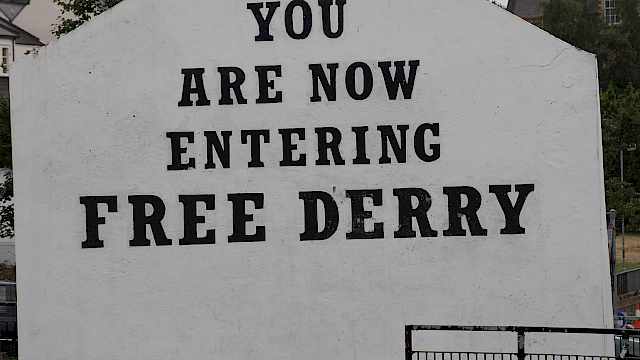

These processes remain visible now. Disaffected republicans use antagonism around policing as a means of attracting support from new members, while the flag protests and perceptions of the erosion of unionist culture attract young unionists toward loyalism.

It is the sense of belonging, affiliation and connectedness that begins the journey that leads to ideology.

While radicalisation is often viewed as an ideological process, it may help to view it as a social process. It is the sense of belonging, affiliation and connectedness that begins the journey that leads to ideology.

In other words, it is not ideological zeal which drives the individual into the arms of an extremist group, but the affinity with the group that drives the individual to the ideology.

2. Involvement can be a reaction to perceptions of injustice

The young Northern Irish men and women who joined paramilitary groups consistently reported how they lacked any deep political or ideological understanding before they became involved with them.

Instead, they were moved to become involved in response to perceptions of injustice, threats from the other community, or experiences of discrimination or violence from the other community or the British State, usually via the actions of the security forces.

3. Attractive alternatives can pull people away from involvement

Family and social networks can push and pull in different directions: The same conditions that attract people to extremist groups can also pull people towards groups which can guide them away from extremism to more prosocial activities.

Countermeasures to protect against engagement should therefore include the provision of alternative groups which are attractive to susceptible young people.

Likewise, using role models to deliver pro-social messages via social and conventional media could help those vulnerable to threat and uncertainty from shifting towards extremist or populist outlooks.

4. Sustained involvement can lead to being bound to the group

When people invest so much and suffer great loss for a group and its political goals, they can become fused with the group and fellow members.

This process of encapsulation within the group reduces contact with the world outside and can lead to a risky shift towards greater extremism.

This isolation promotes greater moral certainty about the group’s ambitions, feelings of empowerment and self-efficacy, coupled with increased dehumanisation and moral disengagement that allows the justification of violence.

This justification offers psychological protection against the negative mental health consequences related to engaging in organised killing, which is vitally important in the ability of the person to sustain their militant career.

5. Burn out and stress can push people to leave

Engagement in extremist violence creates trauma for both the perpetrators and their victims.

Consequently, burn out and stress are factors which play a role in pushing people to leave armed groups (if they have available routes out).

6. When violence is viewed as counterproductive, support for alternatives grows

Those who sustained their membership in armed groups beyond the Good Friday Agreement viewed contemporaneous and past violence as an effective means to bring about social change for their community.

Accordingly, when violence was viewed as counterproductive, futile or antisocial, support for non-violent or political action grew.

7. Imprisonment maintains extremism ...

Twenty to 30,000 Northern Irish loyalist and republican paramilitaries were incarcerated during the Troubles. Even today, issues around imprisonment and prison conditions are key factors in sustaining support among dissident republicans.

For most interviewees, imprisonment involved being concentrated together on segregated wings with members of their particular armed group.

These conditions created the space to develop relationships and strengthen activist identities, which sustained engagement.

8. ... but also opens members up to political solutions

Imprisonment also allowed a greater focus on longer-term strategies that shifted the focus away from violent solutions towards political solutions.

This move, from reactive short-term strategies towards more sophisticated long-term political projects, was driven through engagement with education, group discussion, learning negotiation strategies and practical non-violent skills when resisting prison governance, and maintaining safe intergroup encounters within the prison walls.

For many, prison life was transformational and reflective of the post-traumatic growth witnessed in other settings.

These findings demonstrate the importance of creating a prison environment which allows groups of extremists the necessary space and resources to be challenged, to reflect and explore their goals, and to imagine different strategies to obtain them.

Once imprisoned exemplars begin to move in this direction, their status and prototypical image make them powerful influencers within the group to promote transformational change.

9. The motivations that lead to involvement in violence can also justify a move away from violence

Some of the key motivations for making the move away from violence towards seeking a political settlement focused on the desire to create a shared future for Northern Ireland – to create an environment in which youth would not have to continue the cycle of violence, death and imprisonment they had endured.

There was also a desire to rest, recuperate, and rebuild links with family, friends and the wider community that had been diminished through the all-pervading nature of being a paramilitary.

Therefore, while kin ties and social networks play an important role in pulling people into paramilitary groups, they can also offer routes out.

While kin ties and social networks play an important role in pulling people into paramilitary groups, they can also offer routes out.

10. Strategies aimed at challenging extremist ideologies are not necessary if the aim is to reduce violence

It is unlikely that committed extremists will voluntarily weaken the bonds they have to their comrades and the group, or with the sacred values and associated religious, political, or ethno-nationalist ideologies they identify with.

Therefore, creating strategies aimed at reducing a violent extremist’s identity to their group and ideology is difficult and unlikely to succeed. It is also unnecessary if the aim is to create the conditions for militants to simply desist from violence.

11. Desistance can be fostered by removing barriers to disengagement

Helping an extremist to foster new relationships and identities through education and employment, and by rebuilding family bonds, can moderate the centrality of the extremist self.

Just as an extremist’s identity is embedded within their wider collective or community identity, the strong bonds to the community which initiated their engagement in pro-group antisocial behaviour can also support pro-group prosocial behaviour.

In other words, there is more you can do to help your community than pick up a rifle.

A continued commitment to the community can therefore be harnessed to promote disengagement from extremist violence.

12. Reducing stigma and providing economic alternatives are key

Many of the paramilitaries, and particularly the loyalist paramilitaries, felt stigmatised in post-agreement Northern Ireland. This stigma can have a negative impact on employment prospects, financial security, and both psychological and physical health.

The relationship with stigma and extremism is complex and stigma may play a role in maintaining engagement, by leaving people with few options to leave.

Likewise, it could make re-engagement more likely for those that have left militant groups if they cannot find legitimate means to support themselves and families.

Alternatively, it could cause some to leave if they have options to join a group or create an identity with a better social status through family, education or employment.

Therefore, reducing stigma, facilitating the rebuilding of relationships outside the organisation, and providing opportunities for legal economic activity and self-development are central to desistance.

Read more

- Ferguson, N., McDaid, S. and McAuley, J. W. (2018). Social movements, structural violence and conflict transformation: The case of Northern Irish loyalist paramilitaries. Peace & Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 24, 1, 19–26.

- Ferguson, N. and J. W. McAuley (2017). Ulster Loyalist Accounts of Armed Mobilization, Demobilization and Decommissioning. In L. Bosi and G.De Fazio (Eds.), The Troubles: Northern Ireland and Social Movements Theories (pp. 111–128). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Ferguson, N. (2016). Disengaging from Terrorism: A Northern Irish Experience. Journal for Deradicalization, 6, 1–23.

- Ferguson, N. and Binks, E. (2015). Understanding Radicalization and Engagement in Terrorism through Religious Conversion Motifs. Journal of Strategic Security, 8, 1, 16–26.

- Ferguson, N., Burgess, M., & Hollywood, I. (2015). Leaving violence behind: Disengaging from politically motivated violence in Northern Ireland. Political Psychology, 36, 2, 199–214.

- Ferguson, N. (2014). Northern Irish Ex-Prisoners: The impact of Imprisonment on Prisoners and the Peace Process in Northern Ireland. In A. Silke (Ed.), Prisons, Terrorism and Extremism: Critical Issues in Management, Radicalisation and Reform (p. 270–282). London: Routledge.

- Ferguson, N., Burgess, M. and Hollywood, I. (2008). Crossing the Rubicon: Deciding to Become a Paramilitary in Northern Ireland. International Journal of Conflict and Violence. 2, 1, 130–137.

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2024 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)