While many people have observed that religion is in decline in some parts of the world, less have noticed that the nature of religion has also been changing – especially since the 1980s. What we have been seeing is a gradual ‘hardening’ of religion, with more extreme, fundamentalist forms growing in influence, and more moderate, mainstream forms declining.

Why has this happened, and could it be that legislators, inspired by an ideal of ‘religious freedom’, have unwittingly been complicit?

Extremist vs moderate religion

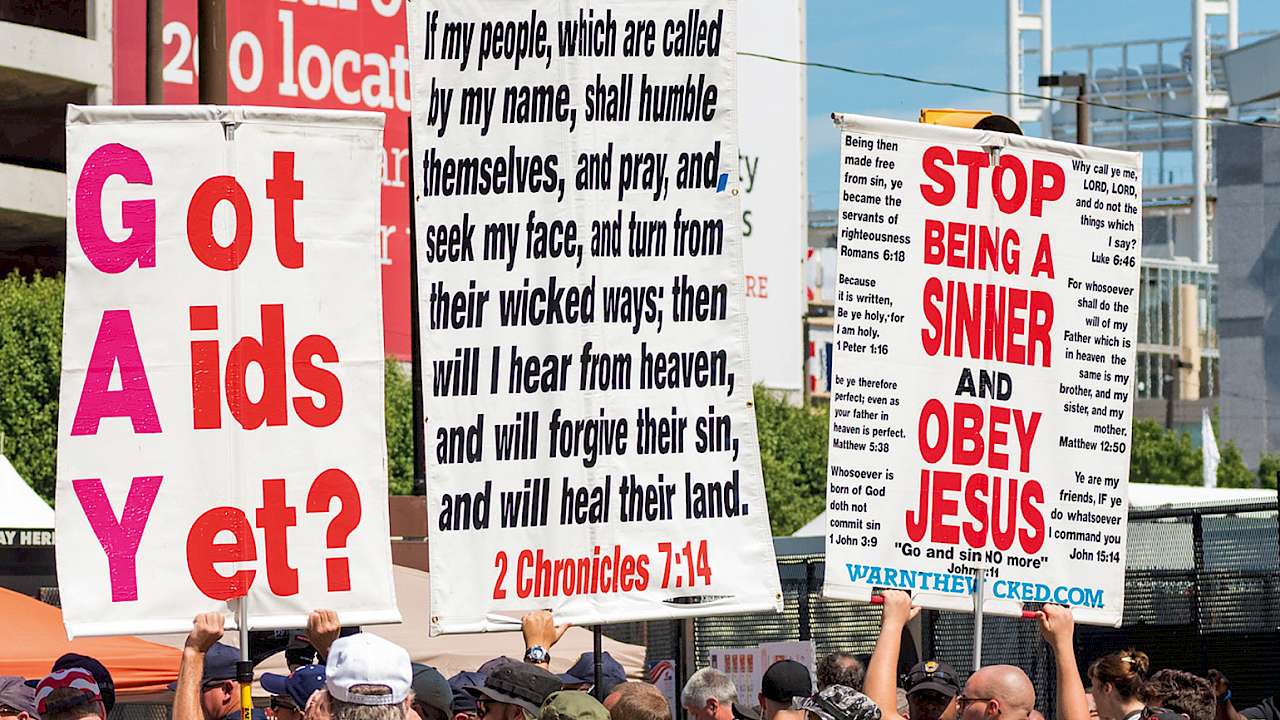

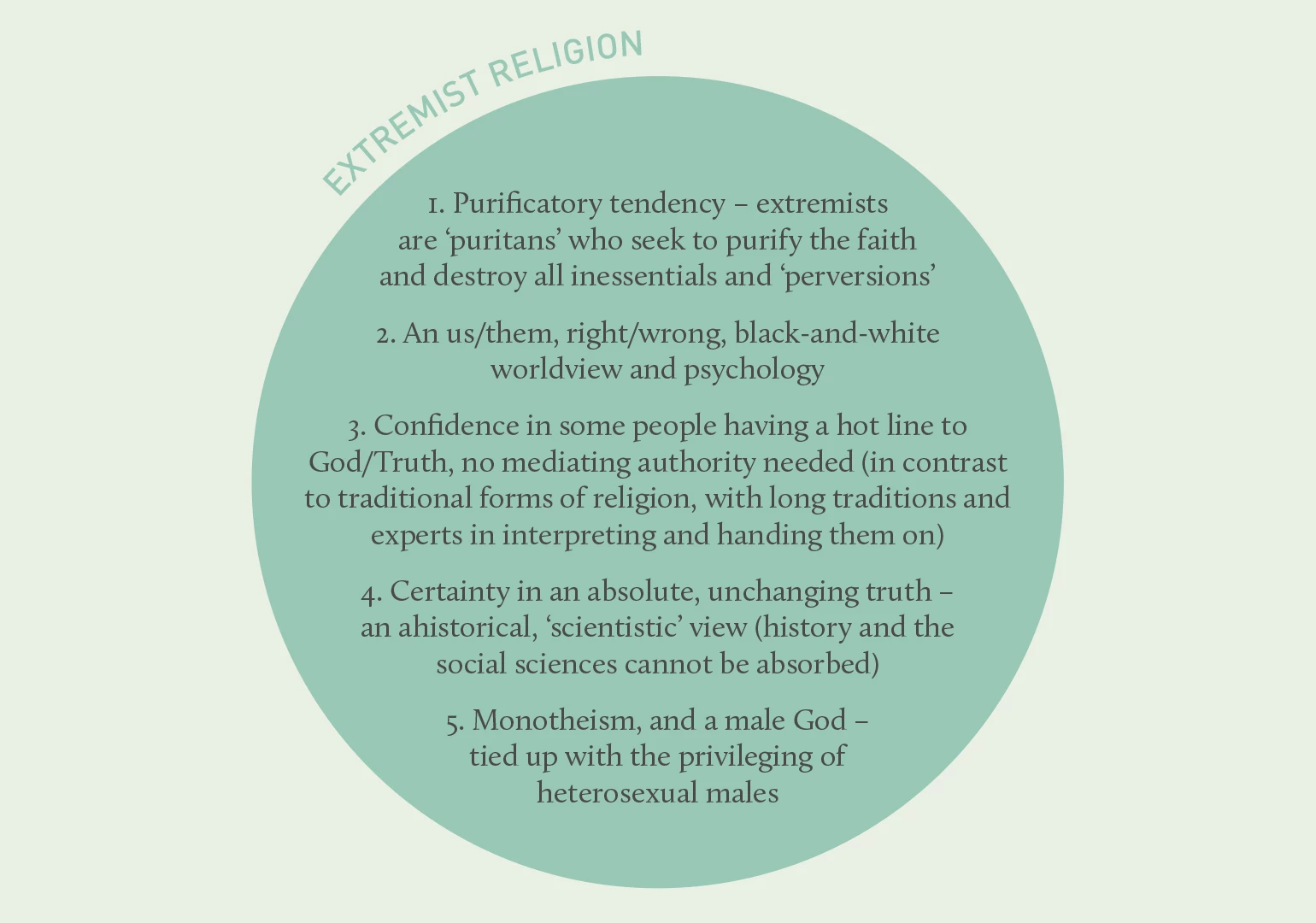

I use the words extremism, fundamentalism, and sectarian or illiberal religion to refer to the same phenomenon. Religious extremism is of course not the same as violent religious extremism, which is a small subset of it. Synthesising a massive amount of research on the phenomenon, we can define it as that form of religion which maintains that:

- there is only one body of truth (deriving directly from God/a higher being)

- that only one particular group has access to this truth

- that the truth can be stated in clear, fundamental propositions

- that all who disagree and disobey are enemies of God.

The research also reveals the following dynamics and tendencies in extremist religion:

The dynamic of extremism

My characterisation of extremist religion would meet with quite wide agreement amongst scholars of religion. What is not yet as widely accepted, but what I believe to be supported by the evidence, is that there is, in every monotheistic religion, an extremist dynamic which operates so long as nothing – such as the countervailing force of moderate religion, or government intervention – checks it. This extremist dynamic operates for a number of reasons.

First, ambitious individuals setting themselves up as religious leaders can always purify a religion a bit more and there is always a motive to do so: the people who set themselves up as the purifier claims to be more obedient than the rest, he is a more courageous defender of costly truth. He can then make a power grab, perhaps through schism.

Second, extremists can never go backwards/liberalise and say they were wrong because they claim to know the truth, a truth which is unchanging. To admit fallibility brings the whole thing crashing down and with it one’s own authority – it all hangs or falls together.

Third, to prove themselves obedient, fundamentalist followers have to follow: when the leader says jump you are meant to jump – even to the point of death. A few really will. So, well-organised fundamentalist religion is often more immediately effective than liberal forms of religion, which have to broker agreements and cannot simply order people to obey.

Finally, opposition is confirmatory; it just proves that the group is right – the fact that ‘the world’, the ‘secular authorities’ and moderate religion (‘the liberals’) oppose them is what they need and expect. Extremist identity is created in conflict and depends upon it.

Moderating forces

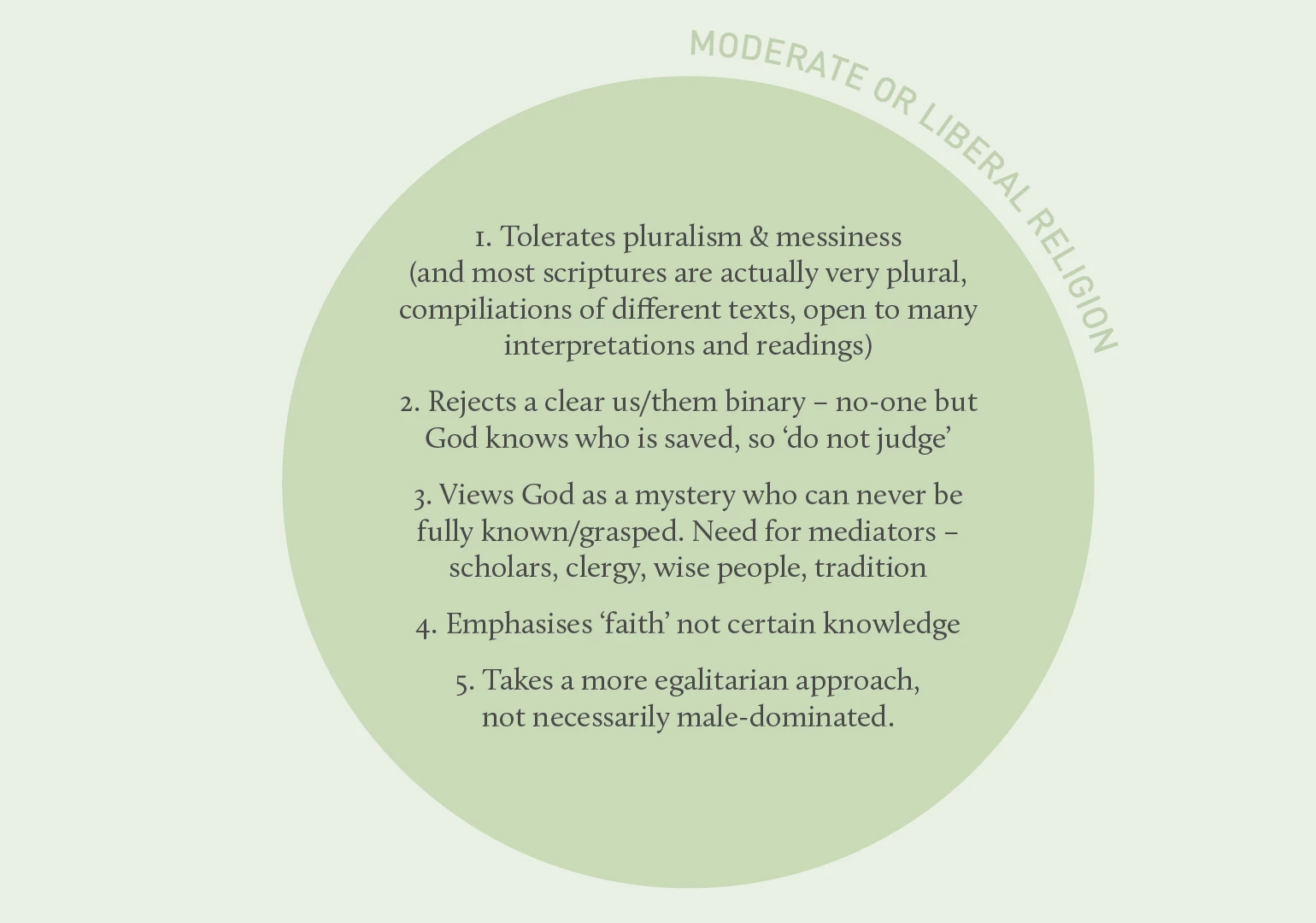

In much of history, the extremist dynamic does not take over in a religion because it is checked by moderating forces. These forces can be internal (push back from moderate majorities and leaders) and external (e.g. political rulers’ patronage of moderate forms and opposition to extremist forms). Although the moderating forces will differ according to the religion, a country and its history and constitution, we can identify a number of important moderating elements. These are particularly effective when the ‘secular’ power has legitimacy with the populus:

- Some system of state support, oversight, or funding (e.g. religious establishment and parliamentary oversight of the Church of England; state funding of the churches in countries like Denmark and Germany)

- Strong ties which bind religion to wider society, and entry points into that society, e.g. in relation to schools (good RE, moderate faith schools), hospitals (chaplains), or everyday life (e.g. religious weddings and funerals as a norm).

- A good relation between religion and mainstream education (e.g. religious leaders are trained in universities, have a high level of education; and good RE is taught in schools to all).

- Clergy do not dominate a religion; there are forums and institutions for lay decision-making; ordinary religious people’s views are represented and taken seriously; clergy serve lay people rather than vice versa.

- Women have real power in the religion and men cannot dominate them.

- Transparency in how religions are led and run; accountable religious leaders. Good relations between religious and political leaders and leaders in civil society.

- Moderate forms of religion are respected and protected by society and state, and extremist bids for power are not aided and supported.

- The natural churn, change, and evolution of all religions is respected and religion is not fossilised by taking seriously the claims of conservatives that religion and its institutions are just as they say, and are unchanging.

Extremist drift is not just Islamic

The growth of extremist wings in religion has been greatly aided and abetted by the fact that governments since the 1970s, not least in the West, have been too weak in countering the creeping influence of fundamentalist minorities. More liberal majorities have been sidelined and ignored.

We can see this not only in Judaism or Islam but in the Christian churches, both Catholic and Protestant. Since the 1970s many have abandoned a liberalising tendency and been taken over by puritanical factions mobilised for the ‘traditional’ (male-led) family and against equal treatment for women and gay people. Conservative leaders have strengthened their power, and liberal wings have shrunk.

In Islam, the dismantling of many of the historic forces of moderation, and the failure to develop new and alternative liberal forms is also part of the background which has led not only to extremism but also to violent extremism in many parts of the world. Some of the factors include the breakdown of traditional forms of religious scholarship and the collapse of various scholarly schools and their ability to contest one another.

Disruptions to traditional forms of authority and to everyday, lived ‘enculturated’ forms of the religion caused by migration have also played a role, as has opportunistic mobilisation around often legitimate grievances. The failure of states to support moderate Islam in effective ways, or to take early and appropriate steps to counter extremism (before violent forms emerge) is also important.

The future of extremism

In most religions, extremism is, as its name implies, just an extreme minority position. It is hard to sustain, and moderate forms of religion which exist in a more open relationship with everyday life and society is numerically dominant. However, when the face of religion becomes increasingly extreme, moderate people vote by leaving the religion altogether. It is this phenomenon, I believe, which explains the rapid rise of ‘no religion’ (which is not the same as atheist secularity) in a number of countries recently.

The problem is that this leaves religion to the extremists, and creates growing tension between religion and the non-religious majority.

Paradoxically, the situation has been exacerbated by the growing influence of the ideal of ‘religious freedom’, according to which ‘secular’ authorities (including legislators) should not just leave religion alone to do its own thing, but should take pains not to interfere with ‘internal’ ‘theological’ matters, and should actively protect religious minorities. Hardline wings of religions have spotted a wonderful opportunity here. In countries which respect religious freedom, they have been able to present their teaching as the ‘authentic’ one of the religion and to have their position protected by law.

Even in the UK, we can see this process at work. It has meant that the once moderate Church of England, for example, has been gradually dominated by its most conservative elements. Since 1975 its leaders have argued – against the opinion of most lay Anglicans – for exemptions from the law which allow them to discriminate on the basis of gender, sexuality, and religion. Parliament, which used to help govern the Church, has pulled back from ‘interfering’, and in the process allowed the hardliners to dominate and the moderate majority to be defeated and decline.

We urgently need to rethink the ‘modern’ way in which we deal with religion. Leaving religion to ‘run itself’ has allowed hardline leaders with much to gain and little to lose to dominate and squeeze moderate majorities. If this process is not to continue, at least three steps need to be taken.

First, we need to stop treating religion as the only sphere which can exempt itself from the laws and regulations which govern other bodies and people.

Second, religions and their leaders need to become transparent and accountable – to the followers and to wider society.

Third, we need to become much better informed about religions and their internal parties and opinions (for example, polling of religious people is now relatively easy, and it reveals where the weight of opinion really lies).

Rulers in the past knew very well how dangerous religion could be. It was the foolish modern belief that religion was, if not a benign force, at least a spent one, that led people to forget.

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.