Over the past decade or so, the importance of developing resilience has been recognised across a range of pressurised performance domains. For example, the United States Army invested $117 million in a scheme to build American soldiers’ psychological resilience. In 2013, on World Mental Health Day, it was reported how building resilience into business enhances both employee wellbeing and performance.

In the past few years, the British Government has invested the equivalent of over half a million dollars in building school children's resilience. It is with these developments in mind that I aim to provide individuals with sound information about developing resilience that is immediately applicable to their work. Specifically, I present a program of mental fortitude training for persons wishing to develop resilience for sustained success.

To begin with, I describe what psychological resilience is. I then outline the main aspects of the training program and discuss its application to enhance performers’ ability to withstand and thrive on pressure. This article summarises how it is possible to facilitate a holistic and systematic approach to developing resilience for sustained success.

What is psychological resilience?

Put simply, psychological resilience refers to the ability to use personal qualities to withstand pressure. As numerous researchers have pointed out, the meaning of the word 'resilience' has evolved somewhat from its Latin origin of resilire translated as ‘to leap back’, to its current psychological-related usage of having a protective effect that involves individuals maintaining their functioning.

The term ‘robust resilience’ is used to refer to its protective quality reflected in a person maintaining their well-being and performance when under pressure, and the term ‘rebound resilience’ is used to refer to its bounce-back quality reflected in minor or temporary disruptions to a person’s well-being and performance when under pressure and the quick return to normal functioning.

In line with both traditional and contemporary meanings of the word resilience, training in psychological resilience – otherwise known as mental fortitude – should be both proactive (i.e., robust resilience) and reactive (i.e., rebound resilience) in nature and target performers before, during, and after stressful or adverse encounters.

Because people’s mental characteristics and outlook change over time, so too does their psychological resilience. Psychologists and others can, therefore, seek to influence – and hopefully enhance – people’s mental fortitude.

The mental fortitude training program

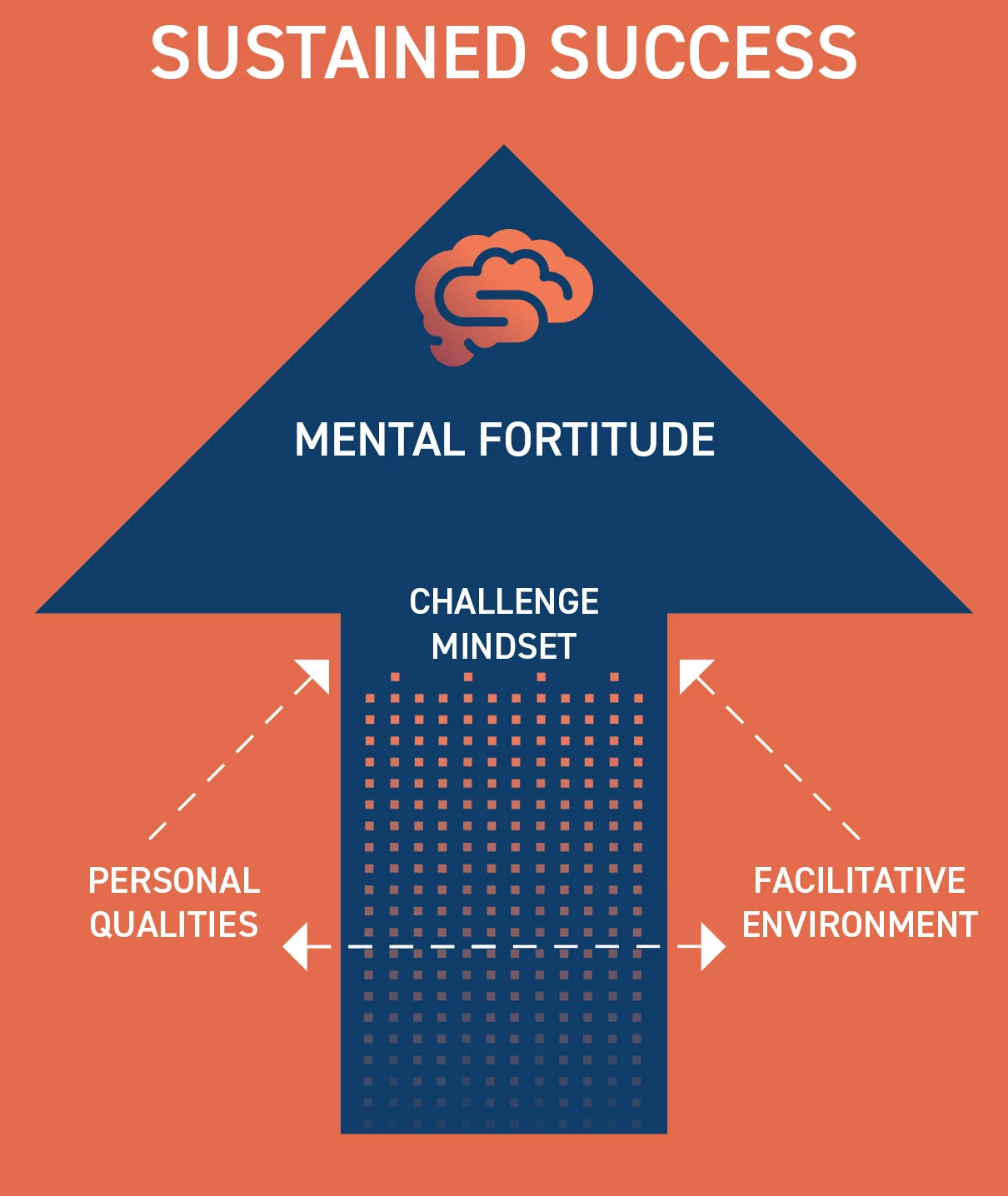

Over the last few years, there has been a burgeoning interest in evidence-based programs and interventions to develop resilience in the workplace for both performance and wellbeing. One such approach that has started to be used across a range of pressurised performance domains (e.g. elite sport, business) is a program of mental fortitude training. Underpinned by resilience-related theory and research, the mental fortitude training program focuses on three main areas – personal qualities, facilitative environment, and challenge mindset – to enhance performers’ ability to withstand pressure (see Figure 1).

Personal qualities

The cornerstone of this resilience training program is, not surprisingly, an individual’s personal qualities, which can be described as the psychological factors that protect an individual from negative consequences. In the resilience training program within the area of personal qualities, we differentiate between personality characteristics, psychological skills and processes, and desirable outcomes that protect an individual from negative consequences. In any moment of time, these personal qualities will likely be tested by stressors and adversities and/or supported by social and environmental resources (see ‘Facilitative environment’ below).

It is important to note that the relevance and importance of these qualities vary across contexts and time. For example, in the elite sport domain, demonstrating resilience to training-related stressors will likely necessitate a different combination of personal qualities than those needed to withstand competition-related stressors.

Another point worth reinforcing is that personality characteristics are less amenable to change than psychological skills, both of which underpin desirable outcomes. Hence, in terms of the developmental potential of psychological resilience, there are aspects of an individual’s psyche that are more malleable than others. Based on this observation, we refer to an individual’s ‘resilience bandwidth’ as an indication of his or her natural developmental trajectory compared to his or her point of highest potential with psychosocial intervention.

With these points in mind, the aim of mental fortitude training is to optimise an individual’s personal qualities so that he or she is able to withstand the stressors that they encounter at any given moment. This aim is, of course, aspirational because any individual, no matter what his or her psychological make-up is, will succumb at some point (his or her ‘breaking point’) to (extreme) adversity and hardship. It is, therefore, imperative to look beyond an individual’s personal qualities to the wider environment in which he or she operates.

Facilitative environment

Although psychological resilience is, by definition, a fundamentally cognitive-affective construct manifested in individuals’ behaviours, it is profoundly influenced by a wide range of environmental factors. Such factors may originate from social, cultural, organisational, political, economic, occupational, and/or technological sources; therefore, any psychological resilience training program should, as much as practically possible, consider the broader environment within which individuals operate.

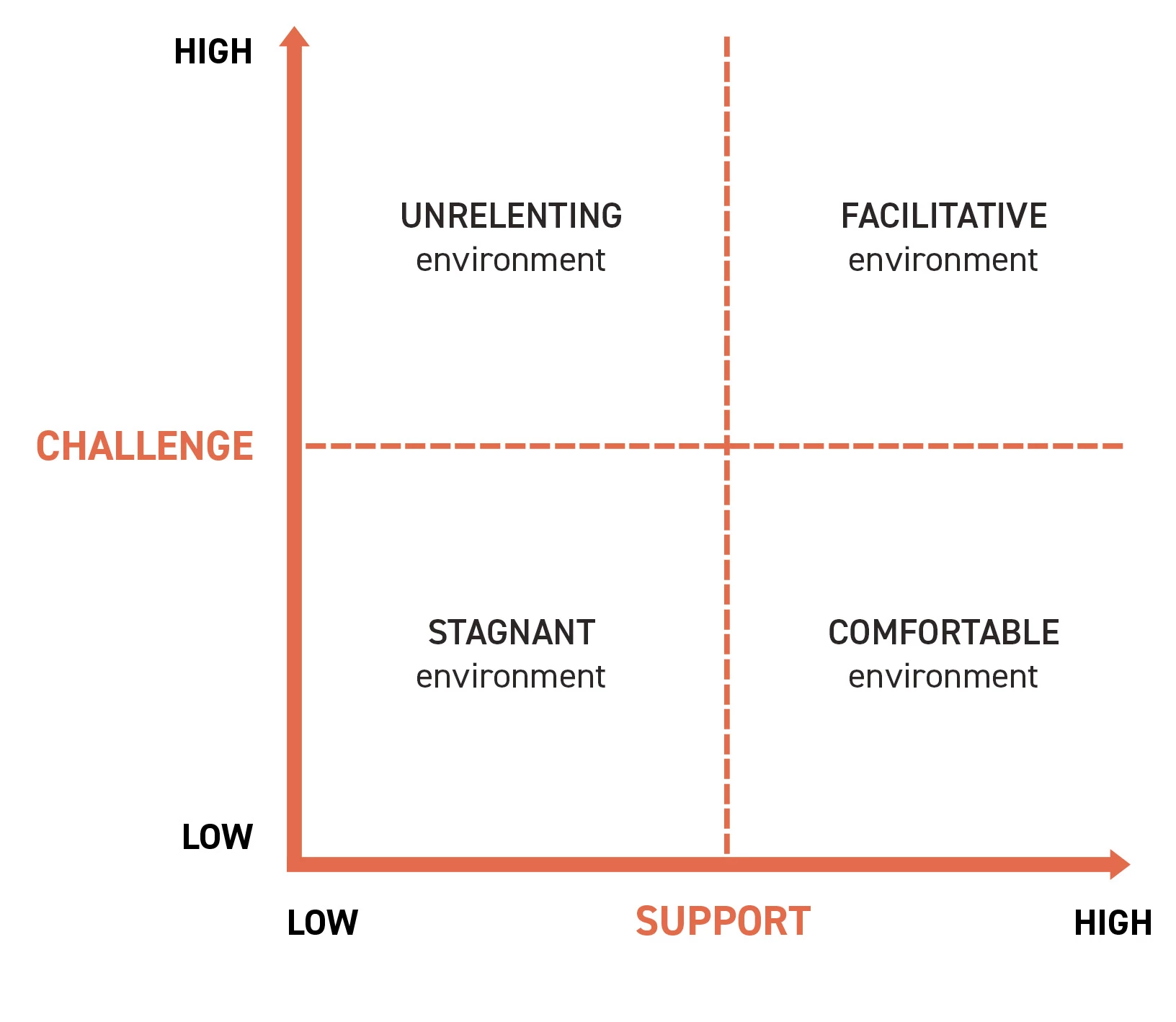

A setting or context that fosters the development of psychological resilience is referred to as a facilitative environment. Since person-environment interactions are highly complex, it is helpful to identify cross-cutting properties that span environmental factors. In terms of developing resilience, the concepts of challenge and support are of fundamental importance.

Challenge involves having high expectations of people and helps to instil accountability and responsibility. The provision of developmental feedback is important to inform about how to improve and, in the context of the present discussion, develop resilience.

Support refers to enabling people to develop their personal qualities and helps to promote learning and build trust.

The provision of motivational feedback is important to encourage and inform about what has been and is effective in developing resilience. Based on the notions of challenge and support, the environment that leaders create can be differentiated between four categories:

- Low-challenge-low-support

- High challenge-low support

- Low challenge-high support

- High challenge-high support.

In the mental fortitude training program, these quadrants are labelled as stagnant environment, unrelenting environment, comfortable environment, and facilitative environment respectively (see Figure 2). Each environment is characterised by different features, but for resilience to be developed for sustained success, a facilitative environment needs to be created and maintained. If too much challenge and not enough support is imposed then the unrelenting environment will compromise wellbeing; conversely, if too much support and not enough challenge is provided then the comfortable environment will not enhance performance.

Challenge mindset

Arguably the pivotal point of any resilience training program is for individuals to positively evaluate and interpret the pressure they encounter, together with their own resources, thoughts and emotions. Largely predicted by (the combination of) an individual’s personal qualities and his or her immersion in a facilitative environment, the ability to evoke and maintain a challenge mindset is of crucial importance in developing resilience. The focus here is on how individuals react to stressors and adversity, rather than the environmental events themselves. As Shakespeare wrote in Hamlet: “There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.”

The mental fortitude training program places emphasis on helping individuals to positively evaluate and interpret the pressure they encounter, together with their own resources, thoughts and emotions.

Central to this is changing negative appraisals into positive or constructive thinking. For those who due to their personalities, background, or surroundings tend to look on the dark side, this can be very difficult. This is why psychological skills and processes need to be practised regularly and why the environment needs to facilitate this development through an appropriate balance of challenge and support.

Fundamental to changing this mindset should be individuals having an awareness of any negative thoughts that make them more vulnerable to the negative effects of stress, and realising and accepting that they have a choice about how they react to and think about events. Interestingly, this has been one of the main approaches used by the US Army to build American soldiers’ resilience.

Drawing in part on cognitive-behavioural therapies, the key to dealing with negative thinking is to regulate one’s thoughts. Although the aim is to engender and maintain a positive evaluation of pressure and a challenge mindset, it is important to recognise that we are all human and will at times engage in negative thinking. Indeed, it may be that automatically initiating the thought regulation strategies in a habitual fashion proves too difficult at times to begin or maintain. In these circumstances, individuals are at risk of becoming trapped in a state of distress characterised by prolonged worry and rumination.

Individuals are at risk of becoming trapped in a state of distress characterised by prolonged worry and rumination.

Individuals should be accepting and non-judgmental about any negative thoughts so that they can begin, when they are ready, to adapt how they respond to such thoughts and beliefs. An important message for those wishing to develop a challenge mindset is that this occurs at multiple levels of cognitive-affective processing, involving positive evaluations and interpretations of the pressure individuals’ encounter, together with their own resources, thoughts, and emotions.

Concluding remarks

In conclusion, this article has outlined a mental fortitude training program for developing resilience for sustained success. Although it is based on a wide-ranging evidence-base, the effectiveness and efficacy of the intervention have not been comprehensively evaluated using research designs that maximise internal and external validity. This training program, therefore, represents a ‘work in progress’ that will undoubtedly be further refined and adapted, particularly with respect to how best to optimise both performance and wellbeing across different pressurised domains. In the meantime, the programme aims to facilitate a holistic and systematic approach to developing resilience for aspiring performers.

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.