It could be argued that we are all threat assessors. Evolutionary instincts enabled our ancestors to recognise predators and, in modern society, similar instincts might tell us to avoid dark alleys or dense crowds.

Yet few of us would consider ourselves professional threat assessors. Although assessors have different backgrounds, from law-enforcement to psychology, they are charged with a similar task: To evaluate whether an individual who poses a threat of violence will indeed commit violence.

Over the last 30 years, this task has developed into a profession. There are now associations for threat assessment professionals, conferences and training courses, and even a journal, the Journal of Threat Assessment and Management. But how do these developments pay off in practice? Does professional experience lead to better quality assessments?

To examine this question, we asked threat assessment professionals and laypersons to participate in a study in which they had to assess three fictitious cases. The cases reflected different domains of violence – domestic violence, public figure violence, and workplace violence – and described the context in which the threat evolved as well as the behaviours and characteristics of the person posing the threat.

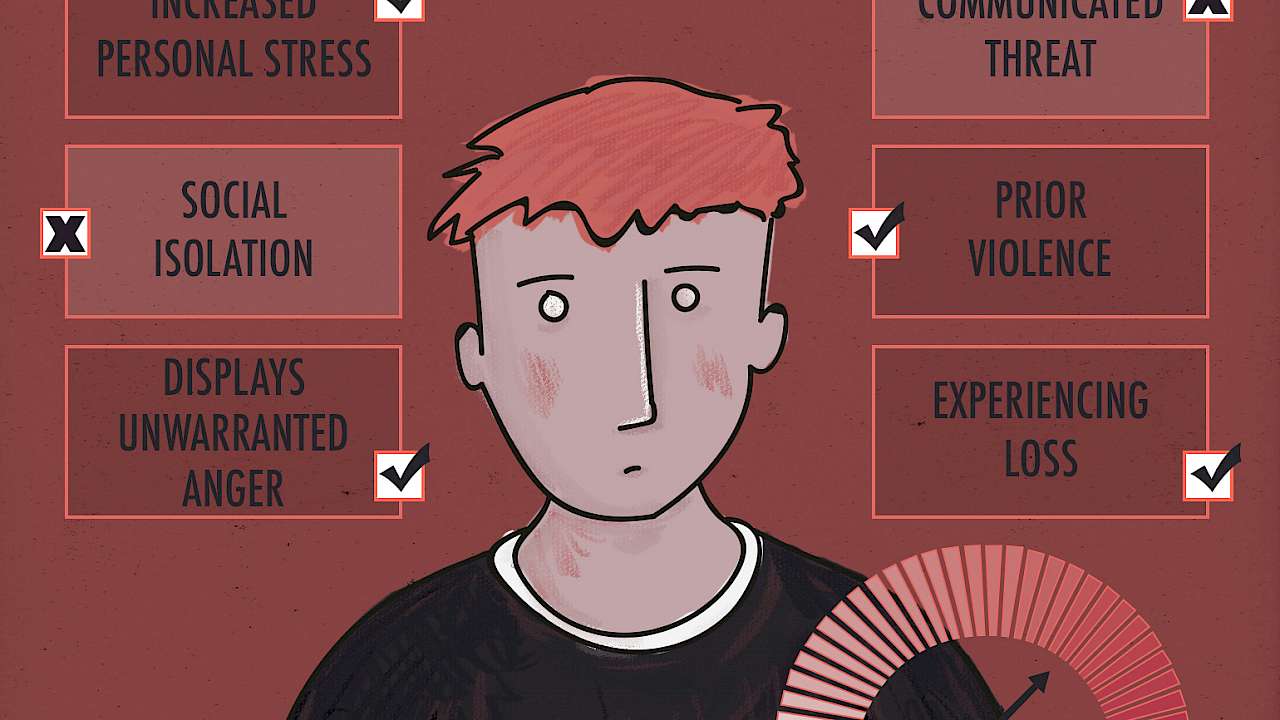

Participants had to assess the risk of violence in each case. Strikingly, the groups did not differ in their assessments. Professionals and laypersons had similar beliefs on what information signalled risk (e.g. prior violence, a communicated threat, experiencing loss) and what information mitigated risk (e.g. being liked by others, playing sports).

One way of explaining this outcome is that intuition enables people to recognise danger when faced with it, regardless of professional experience. If this is the case, then why are professionals needed to assess threats of violence?

It turns out there are several reasons. One reason is that professionals, compared to laypersons, agree more with one another on their assessments.

Clearly, a conclusion about a case should depend on the information on that case, not on the person evaluating the case. Thus, agreement among professionals should be seen as a measure of quality.

A second reason is that, when given the opportunity to request additional information to improve their assessment, professionals requested more relevant information. They sought to engage in a more comprehensive and less biased information search.

This result fits well with theory and research showing that experts, whether they be chess grandmasters, physicians, or police officers, are particularly good at identifying critical cues in massive data. In other words, professionals are better at knowing what information to look for.

Experts are particularly good at identifying critical cues in massive data. In other words, professionals are better at knowing what information to look for.

Interestingly, the latter finding suggests that if one would develop a checklist that summarises what information should be looked for, then laypersons would also be able to make accurate assessments. Part of this reasoning is probably correct. If laypersons were trained to use a checklist, their performance would most likely improve.

However, evaluating potential danger includes more than listing risk factors as present or absent, because risk and protective factors interact with each other. Some factors only exist in combination with others, some factors outweigh or neutralise others, and some factors are so specific that they are only relevant in particular cases.

The interplay between risk factors is not well understood yet on a scientific level, but its complexity underlines where algorithms fall short and expertise becomes necessary. The approach that draws on empirical, informed guidelines but relies on the discretion of a professional for the final judgement is called Structure Professional Judgement and has been proven a reliable method for assessing the risk of violence.

It is important for all parties involved with threats of violence to understand where threat assessment professionals may contribute most. Such an understanding enables the professionals themselves to manage the expectations placed on them. When stakes are high, professionals can face unrealistic demands to predict the future or draw firm conclusions based on little information.

On the other side are those who consult threat assessment professionals, such as prosecutors, judges, or CEOs. Typically placed under time constraints, these officials need to invest their resources well and allocate expertise efficiently.

Most critical, however, is that learning about threat assessment expertise could improve societal safety. Drawing incorrect inferences can be fatal when dealing with risks of violence, making it crucial to appoint the right person to the job.

Read more

The study described in this article is part of Renate Geurt’s doctoral thesis entitled Interviewing to assess and manage threats of violence (September 2017)

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2024 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)