Advances in technologies have enabled intelligence collection and combat engagement from great distances. Decisions made by even junior military personnel can have a direct influence on who lives or dies on the battlefield, a level of responsibility found in few other careers.

The magnitude of the potential consequences arising from these roles, as well as their very nature, lead to many challenges to optimal human performance.

Mission hazards

Multiple health and human factors challenges have been identified in combat-engaged remote warfare units. Stress, sedentary working conditions, rotating shifts, and rapid transitions between combat operations and home life (in essence deploy and redeploy daily, with no end date) can take their toll. These challenges can lead to mental and physical health problems, degraded performance, occupational ‘burnout’, and loss of highly skilled, highly specialised employees.

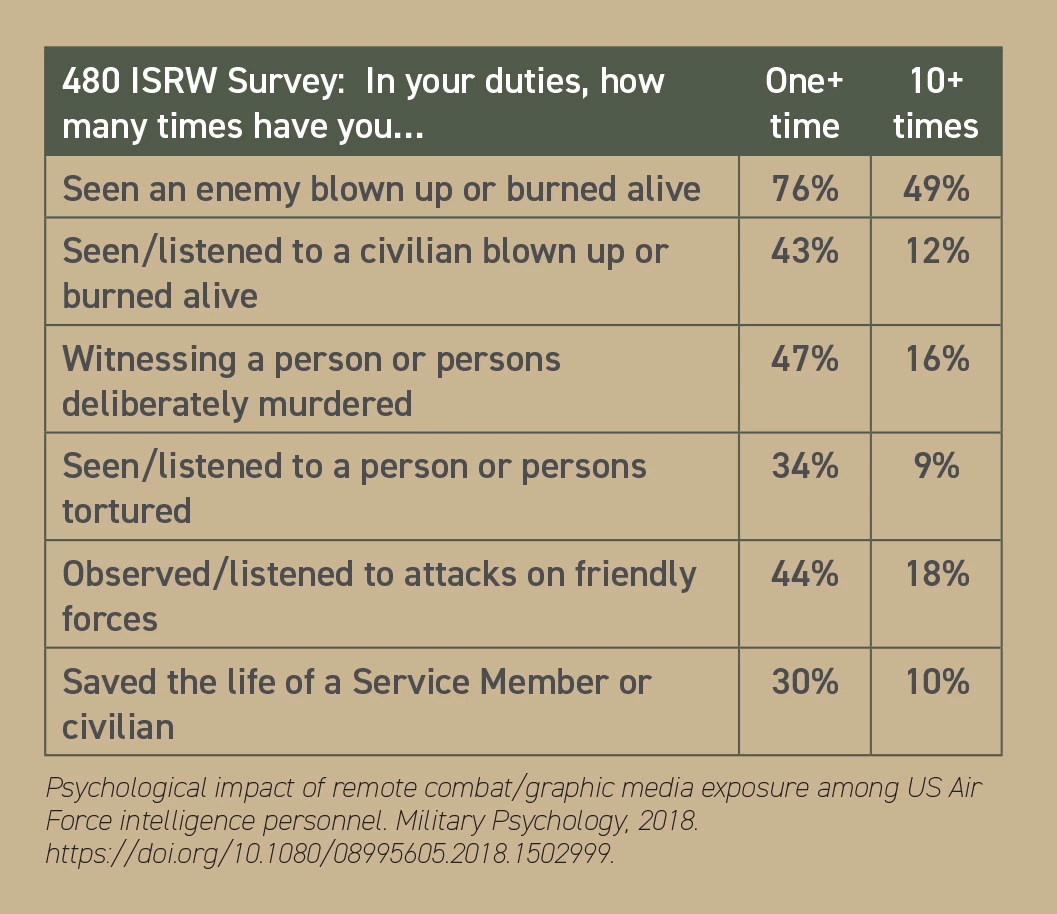

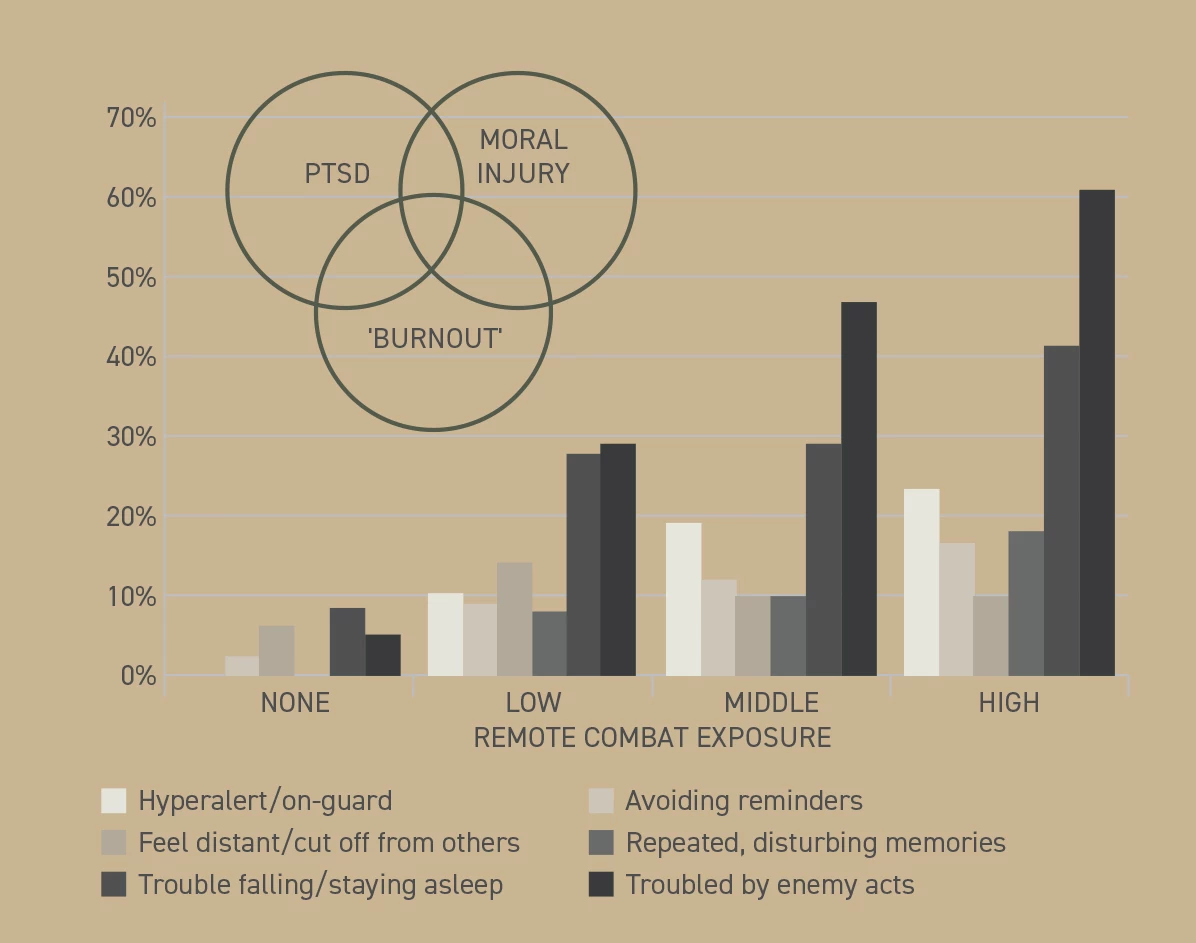

A recent study of US intelligence personnel found that exposures to remote warfare events can also have negative psychological impacts. Rates of exposure to very graphic events were notably high, and analysts with greater amounts of exposure reported more symptoms of traumatic stress, moral injury, and other personal impacts.

This study also assessed strategies that remote warfighters found helpful to prevent and mitigate negative impact and perform well.

Leadership engagement

Remote warfighters reported less distress and were appreciative of supervisors and leaders who understood the challenges of their duties, credibly cared, and checked on their wellbeing on a regular basis. In a military context, these are part of Operational Stress Control (OSC) leadership.

OSC includes additional measures to prevent and mitigate hazards where possible, optimise working conditions, and develop skills in psychological first aid (PFA; initial ‘front line’ assistance and triage to care when needed). Developing OSC skills is recommended for leaders at all levels.

Mission resiliency routines

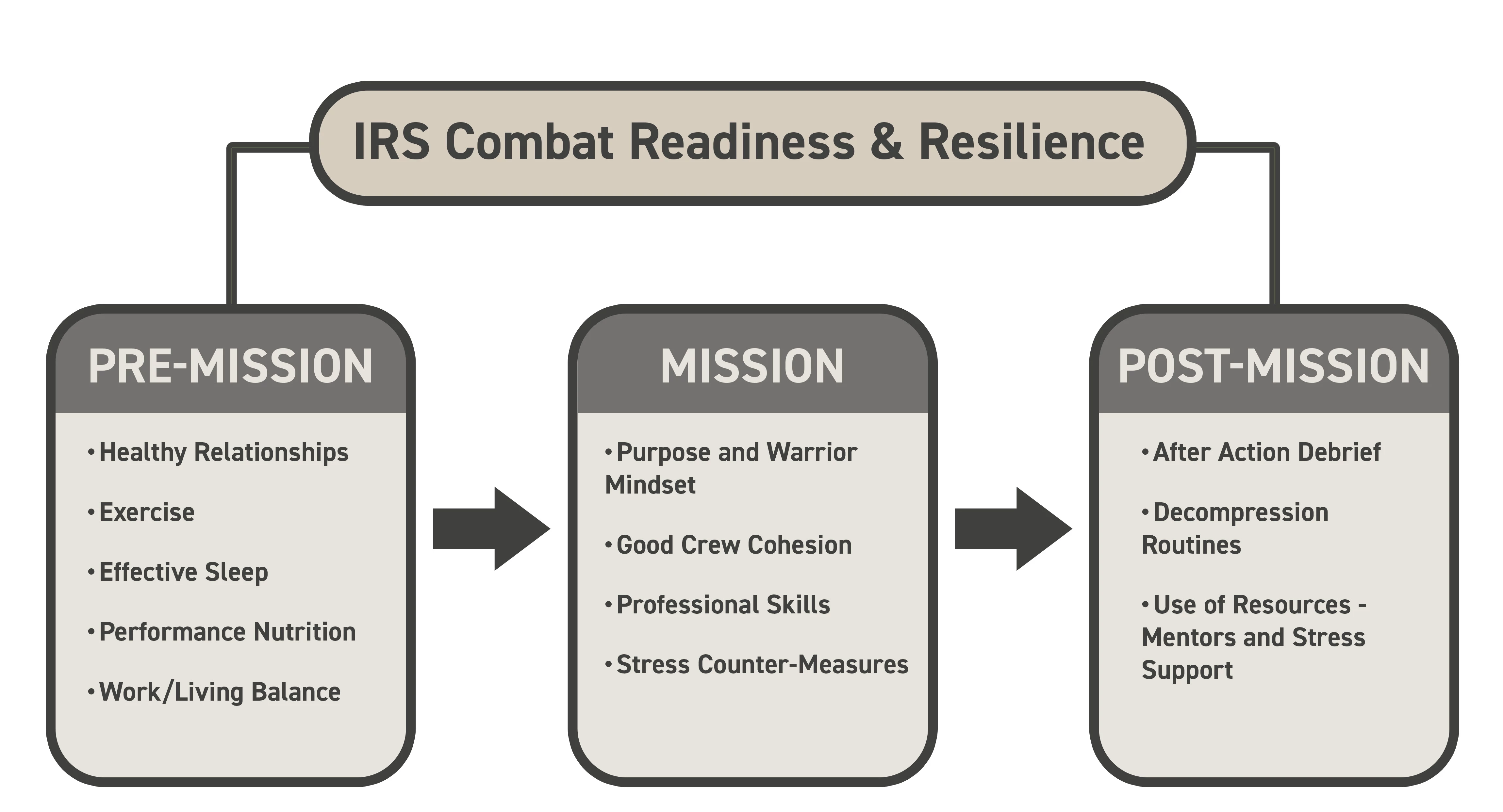

It is possible to surge performance for short durations, however sustaining remote warfighters through months and years of service requires a broader, life-cycle minded approach. The following are positive actions for health and performance sustainment:

- Exercising regularly, preferably three to five times per week consistent with abilities, is important for both physical health and stress relief. Recreational and team activities can add benefits of social interaction and enjoyment.

- Shortages in sleep can quickly lead to fatigue-related errors, potentially costing lives. The majority of us need 7-8 hours of restorative sleep daily. Maintaining good sleep routines is essential, particularly for those working night or rotating shifts.

- Good nutrition can be challenged by availability of healthy options, depending upon work location and hours. Proactively planning and preparing healthy meals ahead of time, such as before the start of a work week, can be very helpful.

- Balance work with positive activities. Frequent exposure to war, death, pain, and human tragedy can cause decreased positive emotions and impact worldview. It is important to plan and engage in positive activities, healthy recreation and relationships, and other steps to maintain work-life balance.

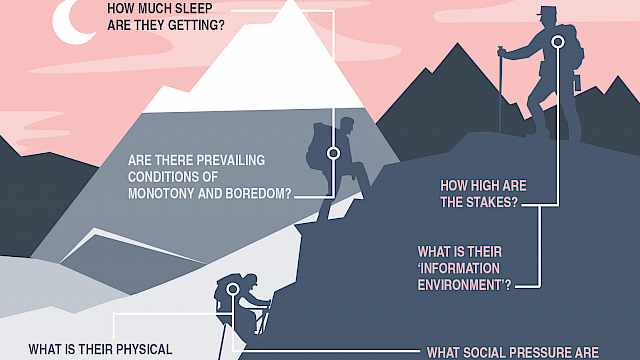

Mission performance

Participation in combat can be momentous and terrible, especially with lives at stake and the demands to do one’s best for the mission, for teammates, and oneself. Remote warfighters are not generally at physical risk, however they are fully alert to the importance of getting it right. Being able to ‘switch on’ during mission is essential, whether for hours of tedious surveillance or moments of crisis actions.

- Purpose and warrior mindset speak to understanding the nature of the work, being grounded in purpose, and committing to best performance. On mission this includes learning as much as possible about the area of interest, background, and objectives for the day.

- Teamwork, cohesion, and good communication supports performance as well as connectedness to identify and assist each other through challenges.

- Stress countermeasures help to remain in a zone optimal for thinking clearly and communicating effectively. Training and practice of ‘tactical breathing’ is a very useful technique towards keeping heart rate and physiological arousal optimal to perform under pressure.

Post-mission

The tempo of operations can vary widely, with many missions being routine, even boring. There can be benefits, though, to having available options to assist personnel following particularly difficult shifts.

- After action debriefing can be beneficial. This can be a brief, informal team discussion of a shift’s events, highlighting praise and opportunities for improvement, which also allows leaders and co-workers to cross-check and support each other. Stress debriefing may be helpful following particularly difficult missions, possibly with assistance of a resiliency support professional.

- Using mentors, supervisors, and trainers to review and improve performance.

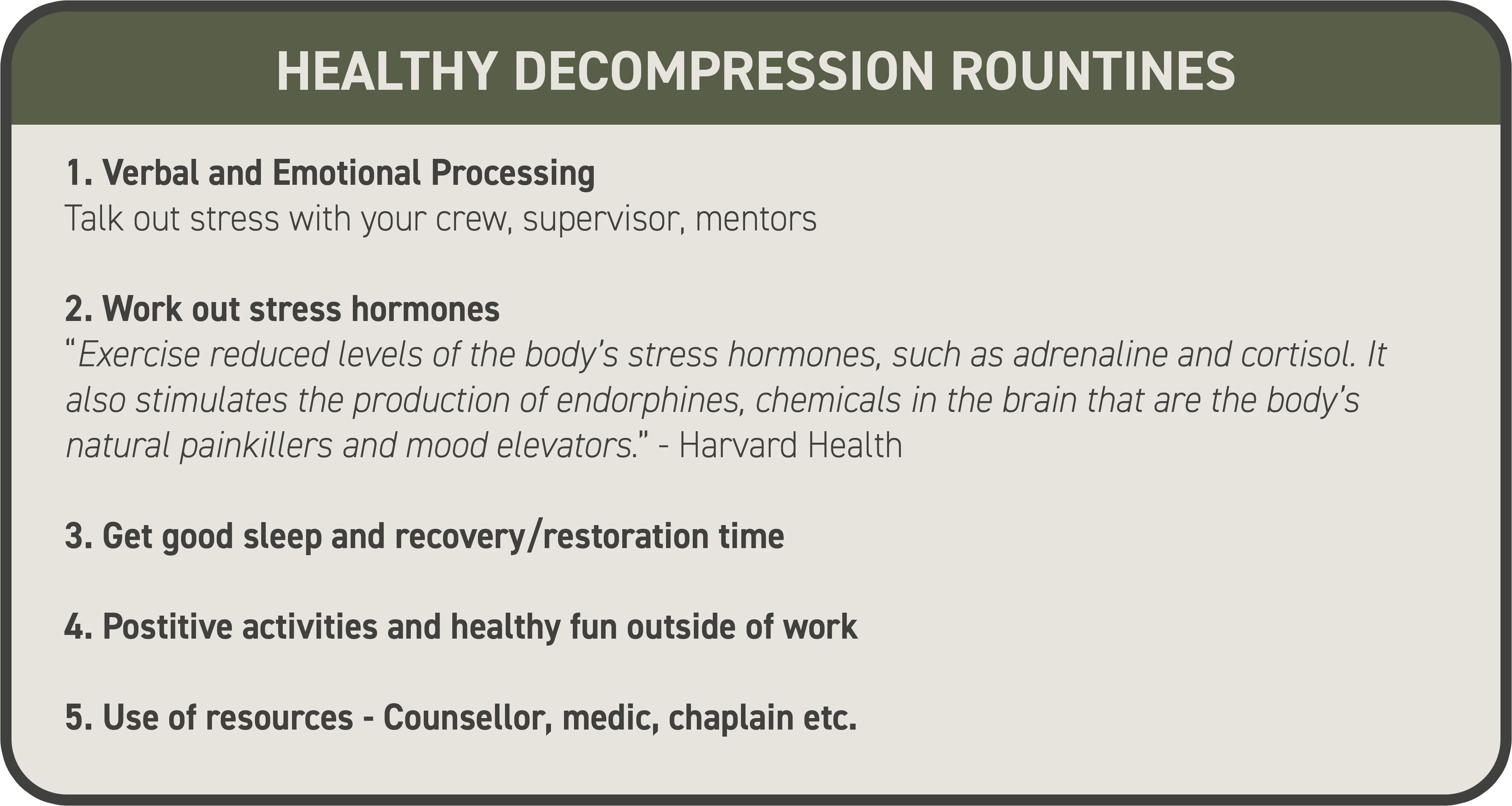

- Remote warfighter should maintain ‘detox discipline’, that is, working through and resolving combat stress as a routine to prevent accumulation. Developing good decompression routines, or activities one finds helpful to process stressful operational events, to transition between work (combat) and home ‘compartments’, to reset and restore body and mind.

Organisational health programme

US remote warfare units have found significant health and mission-performance benefits from having embedded mental health, medical, and spiritual support professionals. These staff have sufficient security clearances and mission knowledge to provide effective, mission-attuned resiliency support services, and consult with leaders for health protection and performance optimisation issues.

As the capabilities for remote warfare continue to grow, so does the need for proactive actions to support resiliency and performance of remote warfighters. The lessons learned from supporting these personnel also provides useful insights for supporting resiliency in other stressful occupations.

Read more

- Alan Ogle, Reed Reichwald, and J. Brian Rutland. 2018. ‘Psychological Impact of Remote Combat/Graphic Media Exposure among US Air Force Intelligence Personnel’. Military Psychology 30 (6): 476–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/08995605.2018.1502999.

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.