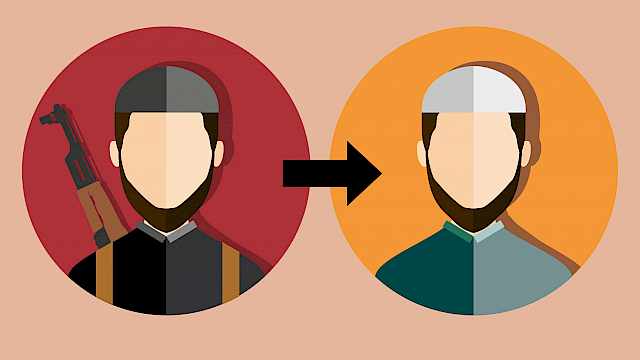

A wide range of actors and approaches fall under efforts to counter violent extremism, from government-led programmes such as those included in the UK’s Counter Terrorism strategy to grassroots initiatives.

Because the factors which lead to violent extremism are complex and wide-ranging, the content of programmes to counter it are diverse. Consequently, the scope and definition of CVE initiatives can be unwieldy. For example, the European Commission, in 2015, defined CVE as ‘all actions that strengthen the resilience of individuals and communities to the appeal of radicalisers and extremism’.

With such broad definitions, it can often be unclear how some programmes, categorised as ‘CVE-relevant’, can be seen to impact on violent extremism.

Despite this, after over a decade of CVE initiatives, a useful picture has begun to emerge, and while there is a strong need for research and evaluation on the impact of CVE programmes, we can begin to point towards evidence of good practice relating to the design, delivery and assessment of some initiatives.

Programme design

There is increasing awareness of the need to carefully target CVE programmes, so they are directed at different stages of the journey into and out of extremism.

Programme delivery

A wide range of actors are involved in developing and delivering CVE interventions. Some programmes are highly centralised and are run and managed by central and local government, others are instigated by civil society actors such as faith or community organisations, NGOs, or former combatants. International bodies such as the European Union are also involved in CVE work.

The extent of involvement from different actors varies; however, most interventions reflect a hybrid approach involving some form of cooperation between government and local actors.

These collaborative efforts are better able to address the complex dynamics of violent extremism but need to ensure they don’t undermine the legitimacy of community-based groups perceived to be working too closely with government.

Programme evaluation

The evidence base about what works in CVE is weak. Few programmes conduct systematic evaluations and many don't make their assessments public. There is also little agreement on what looks like success and how to measure outcomes.

Evaluation can be achieved through three differing approaches. A common approach is by interpreting change in risk factors which operate across a number of levels, including personal factors, such as a desire for adventure or belonging, or need for status; political influences, including a sense of grievance, or strong identification with a political or religious ideology; and group dynamics, such as family or peer involvement in extremism.

To take account of the wider context within which reintegration takes place, it can be helpful to supplement risk-oriented measures by interpreting how well someone is reintegrating. This can include economic integration, such as employment, education or training; social integration, including positive relationships with friend or family networks that do not support extremism; and political integration, such as engagement with democratic systems and increased commitment to wider social and political norms.

Another method of assessing interventions is by examining the process by which organisations develop and deliver their programmes. These can include measures which determine the programme’s integrity, including whether a programme's aims relate to its methods and outcomes and the strength of the evidence that supports this theory of change; delivery agents, including the degree of legitimacy and credibility an intervention provider holds in the local community; and multi-agency working, such as the scope of relationships with relevant statutory and non-statutory organisations and the degree to which the intervention is able and willing to engage with existing multi-agency collaborations.

Good practice in CVE

In a CREST guide on CVE, my colleagues and I have provided case studies that draw out examples of these methods of evaluation and where and how evaluations have worked, or not.

Drawing on these studies, and our evaluation of the wider CVE literature, we have identified several important points to take account of when designing, implementing and evaluating CVE programmes.

It is helpful to consider what constitutes a successful outcome of an intervention, and how this might be assessed and communicated. To help with this, it is important to determine the boundaries of what is CVE-relevant by clarifying which causes of violent extremism interventions are seeking to address and specifying the mechanism by which they are designed to work.

Interventions should also balance a structured approach with the flexibility necessary to respond to unexpected events and shifting local needs. In addition, their design should be based on empirical evidence that informs a theory of change linking aims, methods, and outcomes.

Governments have an important role in designing, funding, and assessing CVE initiatives, as well as building the capacity of community-based actors. Capacity building is helped through fostering local support for interventions by engaging with a range of relevant local and national agencies and stakeholders.

Our guide on CVE provides a range of intervention models which reflect different aspects of good practice in their design, delivery, and assessment, and while ongoing research and evaluation is undoubtedly a priority, there is much to learn from existing practice.

Read more

- Toke Agerschou. 2014. Preventing radicalization and discrimination in Aarhus. Journal of Deradicalization, 1: 5-22. Available at: http://bit.ly/2V2FSia

- Daniel Aldrich. 2012. Radio as the voice of God: Peace and tolerance radio programming’s impact on norms. Perspectives on Terrorism 6(6): 34-60. Available at: http://bit.ly/2CDmqB9

- James Khalil, Martine Zeuthen. 2014. Qualitative study on countering violent extremism (CVE) programming under the Kenya Transition Initiative. USAID. Available at: http://bit.ly/2uCCP4p

- Daniel Koehler. 2013. Family counseling as prevention and intervention tool against the German ‘Hayat’ program. Journal Exit Germany. Journal of Deradicalization and Democratic Culture, 3: 182-204. Available at: http://bit.ly/2Oyr1cB

- Jon Kurtz, Rebecca Wolfe, Beza Tesfaye. 2016. Does youth employment build stability? Evidence from an impact evaluation of vocational training in Afghanistan. In Sara Zeiger (Ed.). Expanding research on countering violent extremism. Hedayah. Available at: http://bit.ly/2I298lz

- Jose Liht, Sara Savage. 2013. Preventing violent extremism through value complexity: Being Muslim being British. Journal of Strategic Security, 6(4): 44-66. Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/vol6/iss4/3/

- Lilla Schumicky-Logan. 2017. Addressing violent extremism with a different approach: The empirical case of at-risk and vulnerable youth in Somalia. Journal of Peacebuilding & Development, 12(2): 66-79. Available at: http://bit.ly/2YttRVb

- Michael Williams, John Horgan, William Evans. 2016. Evaluation of a multi-faceted, U.S. community- based, Muslim-led CVE program. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice. Available at: http://bit.ly/2HLkzyz

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.