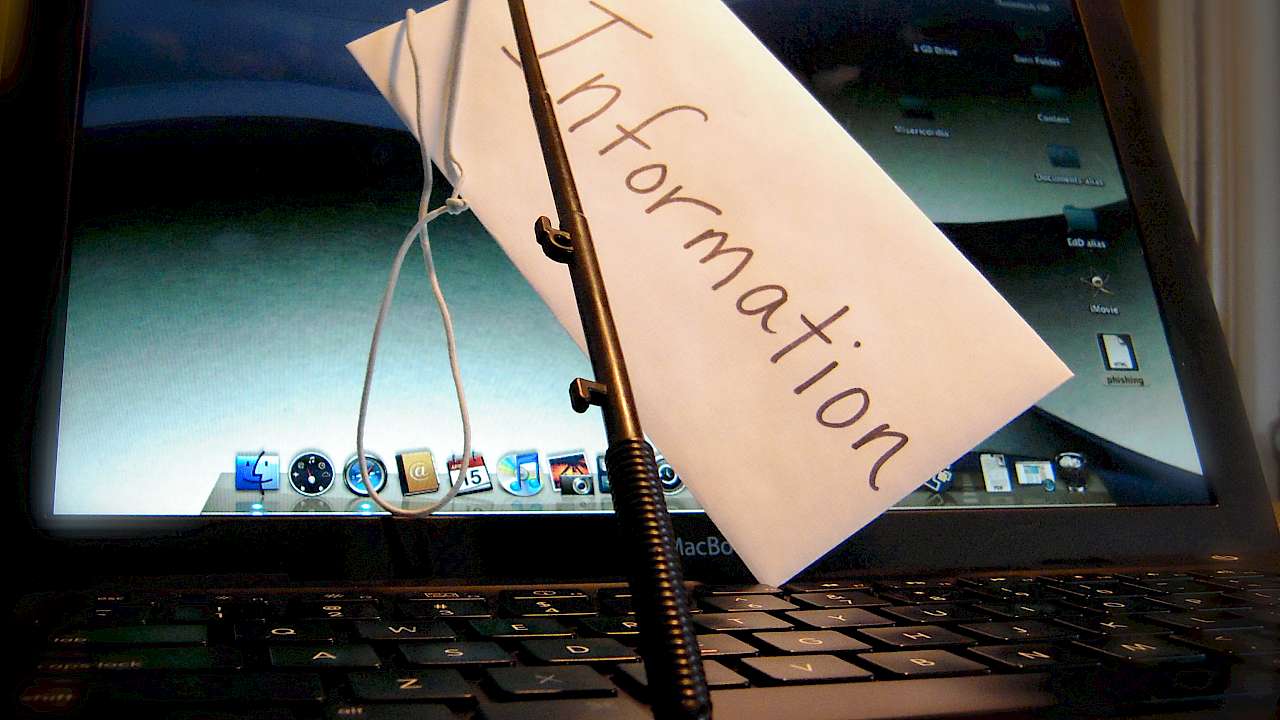

It is easy now to manage almost all aspects of our lives online, from finding a job to booking a holiday. In doing so, we unavoidably have to disclose personal data in the form of bank account details, addresses, where we work and even our hobbies and interests. But in addition to making our lives easier, these online interactions also provide criminals with increasing opportunities to intercept data for their own means. One technique used by criminals is known as phishing, which is where criminals masquerade as reputable individuals or organisations in an attempt to lure individuals into disclosing their personal details.

Phishing attempts typically take the form of emails requesting information or links that prompt an individual to disclose their data. Classic signs of fraudulent emails may be recognisable to most, for example, subjects such as, “You have inherited £1,000,000”, or emails that are filled with poor spelling and grammar. While spam filters tend to remove most unsolicited emails from our inboxes, criminals are using increasingly sophisticated techniques that enable fraudulent emails to bypass the filters and appear to be far less suspicious than they used to.

“You have inherited £1,000,000”

Take, for example, a recent scam that targets homebuyers. After exchanging numerous emails with their solicitor, individuals receive an email that appears to come from their solicitor, asking for the deposit to be transferred. Instead, the email is fake and the money is transferred to the criminal’s account. By hacking into email accounts, criminals can establish that individuals will transfer their deposit and complete their house purchase soon. In turn, they carefully mimic the style and layout of the solicitor’s emails and produce a convincing counterfeit that goes unquestioned by the recipient.

The home buying example highlights a number of specific influence techniques used by criminals to convince people to disclose information. First, trust has already been established between the solicitor and recipient, so an email that appears to be the same as previous correspondence does not arouse suspicion. Second, if the email content aligns with an individual’s expectations, (i.e. the recipient was waiting for a prompt to transfer money), then it is also unlikely to be questioned. Third, house purchases tend to be rare, one-off purchases in contrast to day-to-day transactions. In this situation, an email from a respected figure of authority who handles these transactions daily can exploit someone who may have less experience/knowledge.

It is likely that the success of different influence techniques will also be affected by various circumstances. To date, the evidence of how different contexts influence an individual’s susceptibility to phishing is limited. However, preliminary research suggests that phishing success may be linked to certain personality traits, motivation, attention and workload. Some examples of these include:

- Personality – Extraverts tend to be more social and are more likely to take risks, therefore they may be more likely to respond to fraudulent communications. Individuals who are more open and conscientious are more likely to share information online and respond to authority (see research on this here and here).

- Motivation – Individuals who are tired or lack motivation are more likely to be influenced.

- Attention – ‘Urgent’ communications provoking fear and threat can cause individuals to overlook the giveaway signs of fraud, e.g. the source of the email, poor grammar, and spelling.

- Email load – Research has also found that individuals were more likely to respond to phishing emails when they have a large number of emails to respond to.

In a new CREST guide, we outline the main approaches to phishing and the reasons people click on phishing links, covering:

- Different types of phishing techniques – the approaches used to target individuals and companies

- The various types of influence techniques – communication methods and emotional strategies used to encourage users to click on links

- Strategies that users and organisations can implement to avoid phishing attempts being successful.

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.