___The most persuasive counter messages may instead come from the grassroots level

_

The credibility gap between governments and NGOs, and audiences at risk of radicalisation, is widely accepted. Instead, the most persuasive counter messages may instead come from the grassroots level. The potential benefits of grassroots counter-messaging include:

__- __

- Activists may better resemble audiences physically, culturally or socially, and therefore appear more credible. __

- Activists can demonstrate greater independence from often suspect government financial support. __

- Grassroots activists face fewer limitations on the content they produce. The interactivity of digital media allows messages to be challenged, mocked, recycled and used against their authors. Put simply, messages coming from the grassroots can be funnier and edgier than those from official programmes. _

Grassroots counter-messaging also presents risks for activists and wider society:

__- __

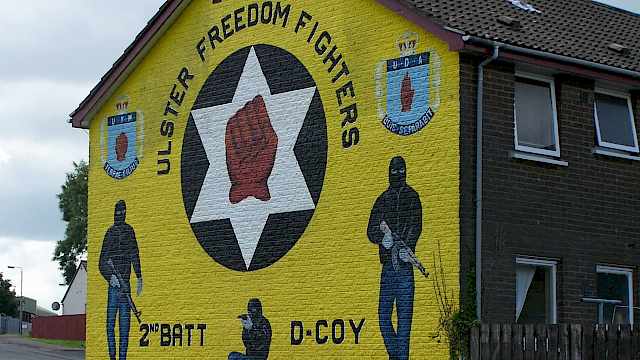

- The closeness of content creators and audiences, and the contentious subject matter, may lead to greater risks for grassroots activists. They are also potentially vulnerable to online harassment, but physical risk is also a possibility when challenging violent extremism locally. __

- A lack of clear guidance on the kinds of messages presented means that counter-messaging may become unconstructive. Counter messages will inevitably be challenging, and may even feature criticism of specific figures; at what point does this go from being socially beneficial to socially harmful? What are the risks that counter messages further embed divisions between extremists and wider societies? _

So far CVE and counter-messaging are considered almost exclusively as a series of organised programmes, and the field is currently dominated by discussions on evaluating success or failure. This approach means that almost nothing is known about the experiences of grassroots activists.

__To fill this gap in existing knowledge, my research aims to answer the following questions:

__- __

- What forms does grassroots counter-messaging take? __

- Who is authoring counter messages and what motivates them? __

- What are the risks of engaging in grassroots counter-messaging? __

- What effects, if any, have activists engaging in grassroots counter-messaging seen? __

- What lessons can governments and NGOs learn from the grassroots, and what can/should the government do to support grassroots counter-messaging? _

To help me answer these questions I have split my work into two strands.

__First, I will concentrate on identifying cases of grassroots counter-messaging campaigns. These could include comparatively straightforward video messages, parody social media accounts, and any other tactics employed against extremist narratives.

__

Second, I will capture the experiences of activists themselves through interviews.

__I do not intend to make a case in support of grassroots counter-messaging over other approaches; counter-messaging will likely always benefit from some level of government support. Instead, I have designed this project around recognising that counter-messaging is more widespread than a narrow set of programmes that can be funded and evaluated.

_____Almost nothing is known about the experiences of grassroots activists

_

At its most basic level, counter-messaging takes place at the interpersonal level, between friends and relations. Online counter-messaging by individual grassroots activists is an extension of these relationships and allows for more personalised messages that are potentially more effective.

__The question remains, however, how both top-down and bottom-up approaches to counter-messaging can learn from each other, and contribute to the overall goal of preventing violent extremism?

" nocookie=1 params="&modestbranding=2&rel=0&enablejsapi=1" >pillory by satirists.The most persuasive counter messages may instead come from the grassroots level

The credibility gap between governments and NGOs, and audiences at risk of radicalisation, is widely accepted. Instead, the most persuasive counter messages may instead come from the grassroots level. The potential benefits of grassroots counter-messaging include:

- Activists may better resemble audiences physically, culturally or socially, and therefore appear more credible.

- Activists can demonstrate greater independence from often suspect government financial support.

- Grassroots activists face fewer limitations on the content they produce. The interactivity of digital media allows messages to be challenged, mocked, recycled and used against their authors. Put simply, messages coming from the grassroots can be funnier and edgier than those from official programmes.

Grassroots counter-messaging also presents risks for activists and wider society:

- The closeness of content creators and audiences, and the contentious subject matter, may lead to greater risks for grassroots activists. They are also potentially vulnerable to online harassment, but physical risk is also a possibility when challenging violent extremism locally.

- A lack of clear guidance on the kinds of messages presented means that counter-messaging may become unconstructive. Counter messages will inevitably be challenging, and may even feature criticism of specific figures; at what point does this go from being socially beneficial to socially harmful? What are the risks that counter messages further embed divisions between extremists and wider societies?

So far CVE and counter-messaging are considered almost exclusively as a series of organised programmes, and the field is currently dominated by discussions on evaluating success or failure. This approach means that almost nothing is known about the experiences of grassroots activists.

To fill this gap in existing knowledge, my research aims to answer the following questions:

- What forms does grassroots counter-messaging take?

- Who is authoring counter messages and what motivates them?

- What are the risks of engaging in grassroots counter-messaging?

- What effects, if any, have activists engaging in grassroots counter-messaging seen?

- What lessons can governments and NGOs learn from the grassroots, and what can/should the government do to support grassroots counter-messaging?

To help me answer these questions I have split my work into two strands.

First, I will concentrate on identifying cases of grassroots counter-messaging campaigns. These could include comparatively straightforward video messages, parody social media accounts, and any other tactics employed against extremist narratives.

Second, I will capture the experiences of activists themselves through interviews.

I do not intend to make a case in support of grassroots counter-messaging over other approaches; counter-messaging will likely always benefit from some level of government support. Instead, I have designed this project around recognising that counter-messaging is more widespread than a narrow set of programmes that can be funded and evaluated.

Almost nothing is known about the experiences of grassroots activists

At its most basic level, counter-messaging takes place at the interpersonal level, between friends and relations. Online counter-messaging by individual grassroots activists is an extension of these relationships and allows for more personalised messages that are potentially more effective.

The question remains, however, how both top-down and bottom-up approaches to counter-messaging can learn from each other, and contribute to the overall goal of preventing violent extremism?

&modestbranding=2&rel=0&enablejsapi=1">Watch on YouTubeCopyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2024 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)