The dynamics of mobilisation in the digital age

We are in an age of protest. From the anti-Brexit ‘Peoples Vote’ marches of 2018, to the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, to the pro-Palestine marches of 2023, collective action has surged to unprecedented levels. In recent years, we’ve witnessed a significant increase in the mobilisation of collective action worldwide, spanning peaceful mass protests to violent extremist action. This surge coincides with the global expansion of internet users, surpassing five billion, including 4.95 million social media users. Concurrently, we have witnessed collective action taking many forms, and occurring both online and offline: for example, online people can post information about social causes, as well as symbols of unity and allyship, recruit new members to their group, crowdsource DDoS attacks, and hack rival organisations.

The online and offline worlds are not separate: people can communicate online whilst engaging in offline action, and vice versa. These social media interactions, sometimes dismissed as trivial, are instrumental in the mobilisation of collective action. Social media serve as spaces for debate, disagreement, and the expression of opinions on social injustices, fostering a sense of shared values among individuals. Indeed, it’s been suggested that the internet is the “greatest critical enabler” for mobilisation: but is there any evidence that people mobilise, at least partially, through their online communications? If so, what are the implications of using online communications data to predict future mobilisation? What ethical considerations arise from developing tools to analyse people's digital footprints for this purpose? Is the internet “the greatest enabler” of mobilisation?

...polarisation on its own was not sufficient for mobilisation.

There are several reasons why communicating via networked technologies might facilitate mobilisation. Social media aids in the development of social groups and networks, providing a platform for online communication of grievances that may lead to polarisation and radicalisation. The internet's capacity for rapid information dissemination and logistical planning further enhances its role in organising, advertising, and serving social-psychological functions in mobilising offline collective action.

Politicians and policymakers have emphasised the role of online polarisation in motivating individuals to join and participate in radicalised groups, which is crucial for collective action. Indeed, in the wake of an increase in extremist action in which social media sites were implicated, politicians took legislative steps to prevent people from becoming radicalised on social media platforms (e.g., the U.K. Online Safety Act 2023). Online polarisation has been cited as a risk factor for mobilisation to violence in the United Kingdom’s and Australia’s counterterrorism strategies. However, there is a lack of specificity in the claims around how and why online polarisation might cause offline mobilisation, and there are no established methods to capture the polarisation of individual users in communications data - and therefore no evidence that directly links an individual’s online polarisation with their offline behaviour. This means there is room for a more granular understanding of the connection between people’s online behaviour and their offline participation in collective action.

The relationship between online interactions and offline collective action is intricate. While online interactions commonly encourage offline activism, some research suggests they can also have a demobilising effect, satisfying the need to act offline, or people may even have disingenuous motivations for engaging in them. These latter online collective actions may be examples of ‘performative’ allyship, which have no significant disruptive offline impact.

The Digital Traces of Mobilisation

Digital traces are digital records of online activities and events, offering valuable insights into the connection between online and offline behaviors. To understand and predict how and why people’s online interactions may be related to their offline mobilisation, we modelled the digital traces left by people engaged in and discussing the anti-Brexit 'People's Vote March.'

The People's Vote March, a significant rally against Brexit, unfolded on October 20th, 2018, drawing an estimated 700,000 participants in London. Online groups formed to encourage people to attend the march, and on social media there was widespread political polarisation, which had an economic fallout and was accompanied by a rise in hate crime. This context provided us with an opportunity to investigate how people’s online behaviour and offline collective action intersected.

We developed new methods to enable us to test and potentially improve the predictive capabilities of psychological theories of collective action, so that we could better explain why online communications could predict offline mobilisation. Conversely, we used psychological theories to inform the design of our algorithms to enhance the algorithms’ rigor, validity, and effectiveness.

...in the 24 hours around the protest event, people left an online ‘digital footprint’ of their participation in offline collective action.

Key Takeaways

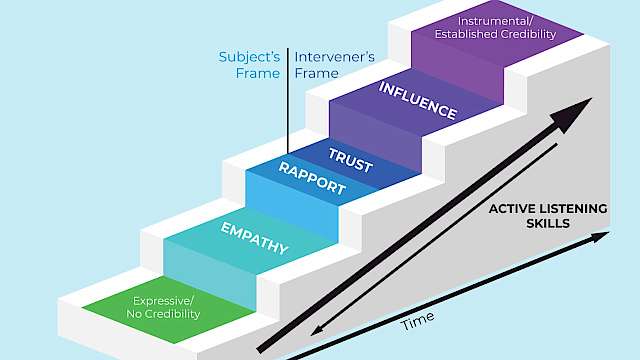

1. Online polarisation alone did not predict mobilisation. Our research modelled online polarisation as communication behaviour, employing an equation capturing changes in people’s online communications data (as a relative intensification of an individual’s posts about a grievance over time). We found polarisation on its own was not sufficient for mobilisation.

2. Validation from others matters. The impact of online polarisation on mobilizing individuals for the People's Vote March depended on the validation (likes) received on their Brexit-related posts. This validation served as a cue, affirming and validating shared perceptions of injustice and fostering a sense of group support. That provided a solid psychological foundation for taking offline action.

3. People leave a digital footprint of mobilisation. We found that in the 24 hours around the protest event, people left an online ‘digital footprint’ of their participation in offline collective action. Therefore, the digital traces left online by people before and during an offline protest event can indicate that they are, or will be, attending that event.

4. Enhancing security through digital traces. The algorithms could be employed to (a) detect potential unrest, (b) provide information to first responders about the potential size of crowds at protest events, and (c) therefore inform crowd management strategies prior to and during large-scale events.

5. Balancing risks and benefits. Algorithms predicting lawful protest pose potential ethical concerns. Our results should be used to safeguard rather than limit lawful protest mobilisation.

Individual’s motivation and self-efficacy for engaging in collective action likely originates online before translating into real-world actions. However, expressing grievances online does not necessarily imply dangerous intentions on an individual level, although it might inspire others. Instead, social media sites act as catalysts for mobilisation, providing spaces for validating grievances and ideas. Rather than censoring expressions of grievances online, which may stifle positive social change, policy should focus on social media sites' algorithms, affordances, and features that drive people together and enable them to validate and legitimise unlawful, violent extremist ideas.

This text is adapted in part from a research article published in the Journal of Personality of Social Psychology: Smith, L. G. E., Piwek, L., Hinds, J., Brown, O., & Joinson, A. (2023). Digital traces of offline mobilization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 125(3), 496–518. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000338

Read more

Awan, I., & Zempi, I. (2020). ‘You all look the same’: Non-Muslim men who suffer Islamophobic hate crime in the post-Brexit era. European Journal of Criminology, 17(5), 585-602. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370818812735

BBC (2018) People’s Vote march: Hundreds of thousands attend London protest. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-45925542

Bliuc, A.-M., Smith, L. G. E., & Moynihan, T. (2020). “You wouldn’t celebrate September 11”: Testing online polarisation between opposing ideological camps on YouTube. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 23(6), 827-844. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430220942567

Brown, O., Lowery, C., & Smith, L. G. E. (2022). How opposing ideological groups use online interactions to justify and mobilise collective action. European Journal of Social Psychology, 52, 1082–1110. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2886

Brannen, S. J., Haig, C. S. & Schmidt, K. (2020) The age of mass protests: Understanding an escalating global trend. Center for Strategic & International Studies. https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/200303_MassProtests_V2.pdf?uL3KRAKjoHfmcnFENNWTXdUbf0Fk0Qke

Del Vicario, M., Zollo, F., Caldarelli, G., Scala, A. & Quattrociocchi, W. (2017) Mapping social dynamics on Facebook: The Brexit debate, Social Networks, 50, 6-16, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2017.02.002

Gill, P., Corner, E., Conway, M., Thornton, A., Bloom, M. and Horgan, J. (2017), Terrorist Use of the Internet by the Numbers. Criminology & Public Policy, 16: 99-117. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12249

Greijdanus, H., de Matos Fernandes, C. A., Turner-Zwinkels, F., et al (2020) The psychology of online activism and social movements: relations between online and offline collective action. Current Opinion in Psychology, 35, 49-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.03.003

Hinds, J., Brown, O., Smith, L. G. E., Piwek, L., Ellis, D. A., & Joinson, A. N. (2022). Integrating Insights About Human Movement Patterns From Digital Data Into Psychological Science. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 31(1), 88-95. https://doi.org/10.1177/09637214211042324

Schumann, S. & Klein, O. (2015) Substitute or stepping stone? Assessing the impact of low-threshold online collective actions on offline participation. European Journal of Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2084

Smith, L. G. E., Blackwood, L., & Thomas, E. F. (2020). The Need to Refocus on the Group as the Site of Radicalization. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(2), 327-352. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691619885870

Smith, L. G. E., McGarty, C., & Thomas, E. F. (2018). After Aylan Kurdi: How Tweeting About Death, Threat, and Harm Predict Increased Expressions of Solidarity With Refugees Over Time. Psychological Science, 29(4), 623-634. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617741107

Smith, L. G. E., Piwek, L., Hinds, J., Brown, O., & Joinson, A. (2023). Digital traces of offline mobilization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 125(3), 496–518. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000338

Smith, L. G. E., Thomas, E. F., & McGarty, C. (2015). “We must be the change we want to see in the world”: integrating norms and identities through social interaction. Political Psychology, 36(5), 543-557. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12180

Smith, L. G. E., Wakeford, L., Cribbin, T. F., Barnett, J., & Hou, W. K. (2020). Detecting psychological change through mobilizing interactions and changes in extremist linguistic style. Computers in Human Behavior, 108, 106298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106298

Statista (2023) Number of internet and social media users worldwide as of October 2023 https://www.statista.com/statistics/617136/digital-population-worldwide/

Thomas, E. F., Duncan, L., McGarty, C., Louis, W. R., & Smith, L. G. E. (2022). MOBILISE: A Higher Order Integration of Collective Action Research to Address Global Challenges. Advances in Political Psychology, 43(S1), 107-164. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12811

UK Parliament (2023) Online Safety Act https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2023/50/pdfs/ukpga_20230050_en.pdf

Usher, J., Morales, L. & Dondio, P. (2019) “BREXIT: A Granger Causality of Twitter Political Polarisation on the FTSE 100 Index and the Pound,” 2019 IEEE Second International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Knowledge Engineering (AIKE), 51-54, doi: 10.1109/AIKE.2019.00017.

Valenzuela S., Correa, T. & Homero Gil de Zúñiga (2018) Ties, Likes, and Tweets: Using Strong and Weak Ties to Explain Differences in Protest Participation Across Facebook and Twitter Use, Political Communication, 35:1, 117-134, https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2017.1334726

Vial, G. (2019) Reflections on quality requirements for digital trace data in IS research, Decision Support Systems, 126, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2019.113133

Copyright Information

Image credit: © Dedraw Studio edited by K.Brennan | stock.adobe.com