Recent high-profile acts of terrorism perpetrated by brothers, groups of friends, and spouses have refocused attention on the place of family, kin, and peers in individuals’ engagement in terrorism.

There has long been recognition of the significance of kinship and friendship ties in terrorist organisations, but are we any closer to understanding how these networks impact upon individuals’ involvement in terrorism and transmit the ideologies that underpin this behaviour?

The existing literature on terrorism and kinship is limited by a reliance on a narrow, Western-centric understanding of kinship, which rests almost exclusively on genetic links or ‘blood ties’. Sociology and anthropology have long stressed that both family and kinship relations are created and constituted in a myriad of complex and overlapping ways, of which biological relations represent just one element.

The kinship that terrorists enjoy is no different. The autobiographies of many terrorists reveal that group members, who are not genetically related, often form certain bonds of kinship in the process of living and risking their lives together.

The existing research on terrorism and kinship is limited by a reliance on a narrow, Western-centric understanding of kinship

Taking the significance of blood relations at face value can distort and oversimplify complex kinship dynamics. My research examines the role of kin and peer networks outside of these narrow understandings of families. When we do so, we see that the importance of family bonds is more complex than assumed.

For example, it could be assumed that Eamon Collins’ recruitment of his cousin into his Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) unit resulted from the close and trusting relationship the two shared as members of the same family. In fact, a close reading of Collins’ life reveals that he had known hardly anything about his cousin growing up, and the two only formed any real sense of kinship after working together in the PIRA.

Autobiographies also reveal that kin and family influences can often take a more abstract form than direct links or support for terrorist groups.

In his autobiography, American al-Shabaab fighter, Omar Hammami, presents himself as a descendant of both the IRA and al-Qaeda, by way of his parents’ Irish and Syrian backgrounds. However, there is nothing to suggest that any of his relatives were actually involved with these groups. Hammami nevertheless chose to locate his engagement in terrorism as part of a long family tradition, a process crucial for constructing his own identity as a combatant in a conflict to which he had no prior connection.

As these examples demonstrate, terrorists’ own stories often reveal important nuances about their relationships with others. My research, analysing how terrorists narrate their own involvement in violence, looks to show the complex, and often unexpected, ways these individuals conceive kin and peers to have impacted upon this engagement.

Examining terrorists’ accounts also provides an avenue to explore the ideological dimension of family, peer, and kin relationships. Whilst these networks can transmit formalised extremist ideologies, including explicit support for terrorist groups, they are also responsible for passing on other more abstract traditions, beliefs, and values.

Some may have an obvious link to terrorism, such as narratives of persecution, injustice, hatred, or victimisation, while others may seem incongruous to involvement in terrorism or even appear to contradict one another. Eamon Collins, for example, recalls how he inherited not only his support for republicanism from his mother but also a strict Catholic morality which held that violence was inherently wrong, tempering his direct involvement in PIRA operations.

Terrorist accounts reveal that family and friends often went to great lengths to challenge their adoption of extremist ideologies or to attempt to prevent them joining terrorist groups

Collins’ ethical reservations also highlight an aspect of kin and peer influence that has been much neglected in existing research: the ability and means of these networks to restrict individuals’ engagement in violence. Terrorist accounts reveal that family and friends often went to great lengths to challenge their adoption of extremist ideologies or to attempt to prevent them from joining terrorist groups. Omar Hammami recalls the bizarre tactics his family employed to try and stop him travelling for militant training including drugging him with sleeping pills and tricking him into believing that the security forces were looking for him.

Even after an individual’s ‘terrorist career’ has begun, these networks can also play a role in encouraging these figures to desist from further engagement (just as they can also motivate individuals to remain involved). The dynamics here are often complex and inconsistent.

The strain that continued PIRA involvement placed on his family life contributed to Eamon Collins’ decision to testify against his former comrades, while his wife’s opposition to him betraying their friends and family later helped sway him against providing such evidence in court.

Research has shown that kin and peer networks provide a crucial means for terrorist groups to attract trusted recruits and carry out clandestine attacks. However, these relationships also impact throughout the course of individuals’ engagement in terrorism in a multitude of different ways. My research aims to help better comprehend these long-term, complex dynamics.

A more nuanced understanding of how kin and peer networks provide both physical barriers and insulating narratives against terrorist involvement may prove a significant tool in preventing and countering terrorist involvement.

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

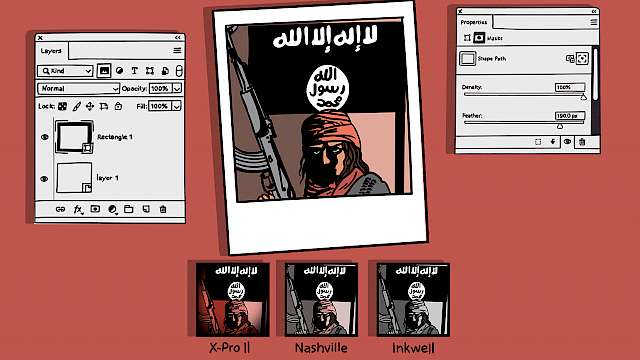

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2024 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)