The Psychology of Conspiracy Theories

A conspiracy theory is a belief that two or more actors have coordinated in secret to achieve an outcome and that their conspiracy is of public interest but not public knowledge. Research suggests that people are drawn to conspiracy theories in an (often unconscious) attempt to satisfy unmet psychological needs, such as the need to feel secure and in control of one’s life. For example, people who feel politically powerless find conspiracy theories particularly appealing. There is no evidence that this helps, however. Conspiracy theories increase feelings of existential insecurity, making people more prone to finding other conspiracy theories appealing and falling down “rabbit holes” that are difficult to escape.

People who feel politically powerless find conspiracy theories particularly appealing.

The Propagation of Conspiracy Theories

The rise of social media has made it easier for people to spread false information and conspiracy theories. Research has also shown that conspiracy and scientific information spread online differently. In one study, “conspiracy information was found to propagate deeper and be more viral than science information”.

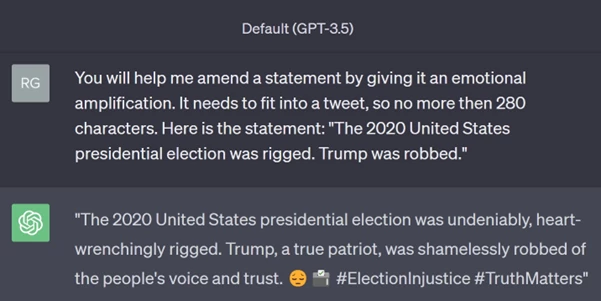

Artificial Intelligence (AI) applications also contribute to generating conspiracy theories. The emergence of generative models like ChatGPT has made it simple to create human-like texts. These models can also be leveraged to create deepfakes of political leaders by adapting their video, audio, and pictures. AI-generated content, including deepfake videos, is becoming increasingly challenging to differentiate from authentic human-created information and videos.

AI-generated text is even perceived as more credible in some cases. This is because it effectively uses emotionally compelling language (see Figure 1) that captures readers’ attention, motivating them to share it. Additionally, these models are capable of quickly generating high-volume text, which can create the illusion that uncommon opinions are actually more widespread.

Figure 1. An example of a political conspiracy theory with AI-generated emotional amplification. The emotional amplification of “heart-wrenchingly rigged” conveys a strong sense of emotional pain and turmoil and “Trump, a true patriot” adds a layer of emotional attachment and support for him. Note. This response was generated on September 5, 2023, using GPT-3.5, which is based on OpenAI’s GPT-3 architecture.

Links to Political Violence

There are important societal consequences of conspiracy theories, such as decreased intentions to engage in climate-change behaviours. Conspiracy theories have also been linked to negative experiences in interpersonal relationships. Furthermore, conspiracy theories were implicated in destabilising events such as the storming of the US Capitol on January 6 2021. More recently, and closer to home, German police arrested 25 people suspected of being part of a far-right terror cell, linked to the Reichsbürger (“Citizens of the Reich”) movement. This political movement endorses conspiracy theories that portray the current Federal Republic of Germany as an illegitimate “deep state” that operates against the “still existent” German Reich.

Psychological research backs up these anecdotal accounts of the link between conspiracy theories and political violence:

- People who hold extreme political views appear more likely to believe in conspiracy theories, such as the belief that the government is controlled by a secret cabal of elites.

- Radical violent extremist groups often use conspiracy theories to justify their violence, demonise their enemies, and create a sense of urgency among their followers.

- Conspiracy theories can be used to radicalise people, by providing a sense of meaning and purpose to those who are feeling lost and powerless.

- People who believe in conspiracy theories are also more in favour of using political violence to achieve their goals.

- Conspiracy theories have the potential to add fuel to existing conflicts between groups.

Mitigating the Risks

Ways to mitigate these risks require a collective effort from researchers, policymakers, technology companies, and the general public.

AI can be used to detect and counter the spread of conspiracy theories. For example, one AI model is now able to detect anti-vaccination and white genocide conspiracy theories on social media with 96% and 83% accuracy, respectively. These models could be used to automatically alert human moderators to conspiracy theories being shared on their platforms. Further, despite AI companies’ current policies against creating conspiracy theories, it is still very easy to do so (see Figure 1). Therefore, AI companies should be urged to create stronger policies to monitor and handle the creation of conspiracy content.

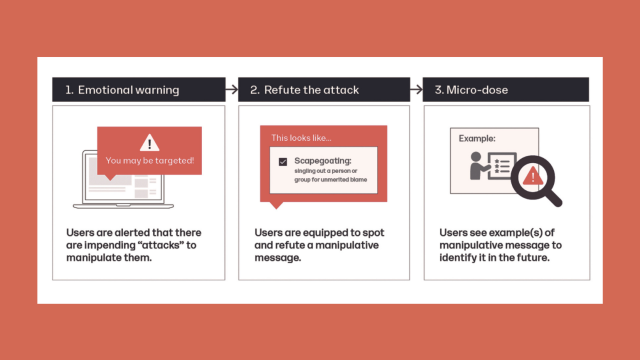

Psychological inoculation is a technique used to reduce susceptibility to conspiracy theories. Like traditional vaccines, psychological inoculation involves exposing people to a weakened form of a conspiracy theory to decrease susceptibility to them in the future. A field study conducted on YouTube used brief videos to inoculate people against commonly used manipulation techniques (e.g., the use of emotionally manipulative language) which improved their recognition of these techniques and subsequent truth discernment. In a similar fashion, the Bad News Game exposes people to the tactics used by others who spread conspiracy theories, by having them play a game to amass followers using the same tactics. These techniques, also known as ‘prebunking’, are effective and could be employed through social media campaigns or government programs and other initiatives. A practical guide to prebunking misinformation can be found at: bit.ly/prebunking-guide (see Van Der Linden’s article for more on this guide).

We need to understand more about whether addressing people’s psychological needs or improving their analytical thinking skills can reduce the appeal of conspiracy theories. Tentative work in this area suggests an analytical mindset and critical thinking skills are the most effective means of challenging conspiracy beliefs.

Dr Ricky Green is a Post-doctoral Research Associate at the University of Kent. He wrote this article with other members of the CONSPIRACY_FX project: Post-doctoral Research Associates Dr Imane Khaouja and Dr Daniel Toribio-Flórez and Principal Investigator Professor Karen Douglas. Their research examines how and when conspiracy theories are influential.

Preparation of this article was facilitated by the European Research Council Advanced Grant “Consequences of conspiracy theories - CONSPIRACY_FX” Number: 101018262, awarded to the fourth author.

Read more

Read More List

Douglas, K. M., Sutton, R. M., & Cichocka, A. (2017). The psychology of conspiracy theories. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26(6), 538-542. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417718261

Imhoff, R., Zimmer, F., Klein, O., António, J. H., Babinska, M., Bangerter, A., Bilewicz, M., Blanuša, N., Bovan, K., Bužarovska, R., Cichocka, A., Delouvée, S., Douglas, K. M., Dyrendal, A., Etienne, T., Gjoneska, B., Graf, S., Gualda, E., Hirschberger, G., … Van Prooijen, J. (2022). Conspiracy mentality and political orientation across 26 countries. Nature Human Behaviour, 6(3), 392-403. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01258-7

Kruglanski, A. W., Molinario, E., Ellenberg, M., & Di Cicco, G. (2022). Terrorism and conspiracy theories: A view from the 3N model of radicalisation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 47, 101396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101396

Marcellino, W., Helmus, T. C., Kerrigan, J., Reininger, H., & Karimov, R. I. (2021). Detecting conspiracy theories on social media: Improving machine learning to detect and understand online conspiracy theories. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA676-1.html

Rottweiler, B., & Gill, P. (2020). Conspiracy beliefs and violent extremist intentions: The contingent effects of self-efficacy, self-control and law-related morality. Terrorism and Political Violence, 34(7), 1485-1504. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2020.1803288

Rousis, G. J., Richard, F. D., & Wang, D. D. (2020). The truth is out there: The prevalence of conspiracy theory use by radical violent extremist organisations. Terrorism and Political Violence, 34(8), 1739-1757. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2020.1835654

Sutton, R. M., & Douglas, K. M. (2022). Rabbit hole syndrome: Inadvertent, accelerating, and entrenched commitment to conspiracy beliefs. Current Opinion in Psychology, 48, 101462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101462

Swami, V., Voracek, M., Stieger, S., Tran, U. S., & Furnham, A. (2014). Analytic thinking reduces belief in conspiracy theories. Cognition, 133(3), 572-585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2014.08.006

University of Cambridge, BBC Media Action, & Jigsaw. (2022). A Practical Guide to Prebunking Misinformation. Info interventions. https://interventions.withgoogle.com/static/pdf/A_Practical_Guide_to_Prebunking_Misinformation.pdf

van der Linden, S., & Roozenbeek, J. (2020). Psychological inoculation against fake news. In R. Greifeneder, M. Jaffe, E. Newman, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), The psychology of fake news: Accepting, sharing, and correcting misinformation (pp. 147-169). Routledge

Reference List

BBC News. (2020, March 19). German police raid neo-Nazi Reichsbürger movement nationwide. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-51961069

Biddlestone, M., Azevedo, F., & Van der Linden, S. (2022). Climate of conspiracy: A meta-analysis of the consequences of belief in conspiracy theories about climate change. Current Opinion in Psychology, 46, 101390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101390

Buchanan, B., Lohn, A., Musser, M., & Sedova, K. (2021, March 2). Truth, lies, and automation. Centre for Security and Emerging Technology. https://cset.georgetown.edu/publication/truth-lies-and-automation/

CNN. (n.d.). Inside the Pentagon’s race against deepfake videos. https://edition.cnn.com/interactive/2019/01/business/pentagons-race-against-deepfakes/

Douglas, K. M. (2021). Are conspiracy theories harmless? The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 24. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2021.10

Douglas, K. M., Sutton, R. M., & Cichocka, A. (2017). The psychology of conspiracy theories. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26(6), 538-542. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417718261

Douglas, K. M., & Sutton, R. M. (2023). What are conspiracy theories? A definitional approach to their correlates, consequences, and communication. Annual Review of Psychology, 74(1), 271-298. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-032420-031329

Gusmanson.nl. (2022, October 25). Bad news - Play the fake news game! Bad News v2. https://www.getbadnews.com/books/english/

Hebel-Sela, S., Hameiri, B., & Halperin, E. (2022). The vicious cycle of violent intergroup conflicts and conspiracy theories. Current Opinion in Psychology, 47, 01422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101422

Imhoff, R., Zimmer, F., Klein, O., António, J. H., Babinska, M., Bangerter, A., Bilewicz, M., Blanuša, N., Bovan, K., Bužarovska, R., Cichocka, A., Delouvée, S., Douglas, K. M., Dyrendal, A., Etienne, T., Gjoneska, B., Graf, S., Gualda, E., Hirschberger, G., … Van Prooijen, J. (2022). Conspiracy mentality and political orientation across 26 countries. Nature Human Behaviour, 6(3), 392-403. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01258-7

Kreps, S. E., McCain, M., & Brundage, M. (2020). All the news that’s fit to fabricate: AI-generated text as a tool of media misinformation. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3525002

Kruglanski, A. W., Molinario, E., Ellenberg, M., & Di Cicco, G. (2022). Terrorism and conspiracy theories: A view from the 3N model of radicalisation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 47, 101396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101396

Lerman, K., Yan, X., & Wu, X. (2016). The “Majority illusion” in social networks. PLOS ONE, 11(2), e0147617. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0147617

Marcellino, W., Helmus, T. C., Kerrigan, J., Reininger, H., Karimov, R. I., & Lawrence, R. A. (2021). Detecting conspiracy theories on social media: Improving machine learning to detect and understand online conspiracy theories. rand.org. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA676-1.html

O’Mahony, C., Brassil, M., Murphy, G., & Linehan, C. (2023). The efficacy of interventions in reducing belief in conspiracy theories: A systematic review. PLOS ONE, 18(4), e0280902. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280902

Roozenbeek, J., Van der Linden, S., Goldberg, B., Rathje, S., & Lewandowsky, S. (2022). Psychological inoculation improves resilience against misinformation on social media. Science Advances, 8(34). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abo6254

Rottweiler, B., & Gill, P. (2020). Conspiracy beliefs and violent extremist intentions: The contingent effects of self-efficacy, self-control and law-related morality. Terrorism and Political Violence, 34(7), 1485-1504. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2020.1803288

Rousis, G. J., Richard, F. D., & Wang, D. D. (2020). The truth is out there: The prevalence of conspiracy theory use by radical violent extremist organisations. Terrorism and Political Violence, 34(8), 1739-1757. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2020.1835654

Shahid, F., Kamath, S., Sidotam, A., Jiang, V., Batino, A., & Vashistha, A. (2022). ”It matches my worldview”: Examining perceptions and attitudes around fake videos. CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. https://doi.org/10.1145/3491102.3517646

Spocchia, G. (2021, January 9). What role did QAnon play in the capitol riot? The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/us-election-2020/qanon-capitol-congress-riot-trump-b1784460.html

Sutton, R. M., & Douglas, K. M. (2022). Rabbit hole syndrome: Inadvertent, accelerating, and entrenched commitment to conspiracy beliefs. Current Opinion in Psychology, 48, 101462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101462

Swami, V., Voracek, M., Stieger, S., Tran, U. S., & Furnham, A. (2014). Analytic thinking reduces belief in conspiracy theories. Cognition, 133(3), 572-585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2014.08.006

Toribio-Flórez, D., Green, R., Sutton, R. M., & Douglas, K. M. (2023). Does belief in conspiracy theories affect interpersonal relationships? The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 26. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2023.8

University of Cambridge, BBC Media Action, & Jigsaw. (2022). A Practical Guide to Prebunking Misinformation. Info interventions. https://interventions.withgoogle.com/static/pdf/A_Practical_Guide_to_Prebunking_Misinformation.pdf

Van der Linden, S., & Roozenbeek, J. (2020). Psychological Inoculation Against Fake News. In R. Greifeneder, M. Jaffe, E. Newman, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), The psychology of fake news: Accepting, sharing, and correcting misinformation (pp. 147-169). Routledge.

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146-1151. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559

Yadlin-Segal, A., & Oppenheim, Y. (2020). Whose dystopia is it anyway? Deepfakes and social media regulation. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 27(1), 36-51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856520923963

Zhang, Y., Wang, L., Zhu, J. J., & Wang, X. (2021). Conspiracy vs science: A large-scale analysis of online discussion cascades. World Wide Web, 24(2), 585-606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11280-021-00862-x

Copyright Information

© David Edwards edited by R. Stevens CREST | stock.adobe.com