My research looks at grassroots efforts to counter violent extremism: who is doing it, how, and what motivates them. As part of this research, I sat down with Ray Hill to talk about the work he does with young people.

Ray isn’t part of any government or civil society programme. He’s 77, retired and works independently. In the 1960s Ray was an active member of the far-right British Movement, but towards the end of the decade, he moved to South Africa. His politics changed after seeing apartheid first hand and, on his return to the UK, he worked as a mole inside the UK far-right for the anti-fascist organisation, Searchlight. He broke cover spectacularly in 1984, telling all in a Channel 4 documentary.

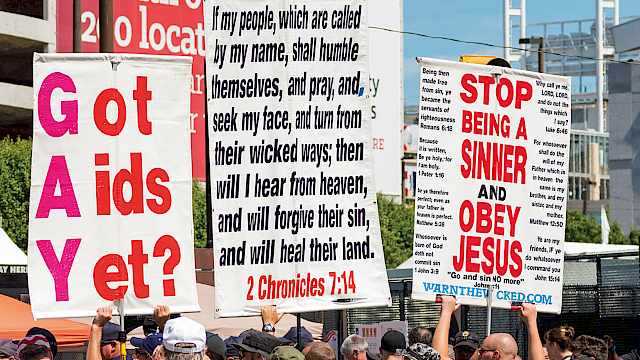

Ray works with young people (16–25) in his local area, directly approaching and engaging them to try and limit far-right influence. He is proud of the work he does speaking to youth groups and religious organisations about the far-right, but those kids aren’t the ones he sees as vulnerable. Rather, Ray describes a local scene of young men (and less frequently women), unemployed or in ‘dead-end’ jobs, ‘universally poorly educated’ and involved in low-level criminality.

When I ask Ray about the opinions he encounters, he gives a typical example:

‘My Dad and my Granddad, and sometimes even my great Granddad, fought for this country and these bastards are giving it away… to people from all over the fucking world. Just giving it away. Nicked it, it’s mine.’

I ask Ray about the likelihood of the young people he works with joining formal political organisations.

I don’t go out my way to praise the BNP, but they did keep them in some sort of check

‘What’s happened, UKIP has syphoned off… the respectable right, leaving this indisciplined often violent and often youthful section, and they, the one time they had their home in the BNP. And don’t misunderstand me, I don’t go out my way to praise the BNP, but they did keep them in some sort of check. Not anymore. They join little groups now, little local groups with a loose affiliation with a similar group in a nearby town. But that’s it. No organised structural, sort of political activity.’

Expanding on this argument, Ray describes some of the young people in his area as being drawn into more violent activities:

‘When you talk about terrorism, which is the extreme wing of what we’re talking about, where does it start? I know youngsters whose favourite occupation is walking around an indoor market…with a fag, and there’s a pile of crew neck jumpers on some Indian’s stall and they shove the fag in the middle of them. It’s terrorism. It’s nascent terrorism.’

When I ask Ray how he challenges the attitudes he encounters, he says it comes down to making a good impression and talking the talk. He describes initiating conversations at non-league football games:

‘All I do is simply strike up a conversation and I’m not bad at that, and wait for some remark being made about a coloured player.’

As I try to get a better idea of the conversations he has with young people, he remembers a decisive incident from his days gold-mining in South Africa that he likes to tell people:

‘The roof came down on me and I was trapped, several thousand feet underground, not a pleasant experience … I got pulled out by a Zulu boy. He came down at massive risk to himself… And the Yorkshire lad, who I thought was a personal friend of mine, did a runner.’

I'm not in any organisation, I don’t have any rules, I just do it off the top of my head, the way it strikes me. I see an in and I jump in

Ray gives the impression that his work would be a good deal harder if he was tied to an official programme or organisation.

‘I’m not in any organisation. I don’t have any rules. I just do it off the top of my head, the way it strikes me. I see an in and I jump in.’

His lack of establishment credentials, as he sees it, are a good fit for the disaffection of those he tries to talk to. But I’m keen to get a better idea of what Ray thinks of more formal approaches to countering violent extremism.

‘I have grave doubts about it because let’s face it, extremism depends on where you’re standing. Some of the terminology is fucking mad. Radicalisation, what you mean like the peasant’s revolt?’

Ray doesn’t think that his kind of background is often represented in official programmes. Although he sees these as ‘well-intentioned and may do some good’, he doubts that those involved could connect with the types of people and places he engages with. So, what drives him on?

I’m 77 years old now. I do this purely out of conviction

‘I’m 77 years old now. I do this purely out of conviction. There’s no financial inducement, I’m as poor as a fucking church mouse, I’m driving a 12-year-old car … I just go out and do it because it’s become my raison d’etre, you know, it’s why I’m here.’

This is not de-radicalisation or counter-messaging as we generally think of it. Ray makes no bones about his lack of government or NGO support. Equally, it is difficult to imagine a narrative as oppositional as Ray’s finding much traction in official circles. Nevertheless, his work is a good illustration of how extremism is being countered outside government and formal CVE programmes.

I conclude by asking Ray how his background as an active member of the far-right relates to his motivation to dissuade young people from following the same path. I ask him directly if he is trying to atone. In response, he says:

‘I think I’ve done fascism more harm than I ever did it good.’

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.